By Baotiao

A Brief Introduction to the HyPer-style Design Referenced by DuckDB's MVCC

DuckDB's MVCC implementation is based on the paper Fast Serializable Multi-Version Concurrency Control for Main-Memory Database Systems. This article will briefly introduce the design philosophy of this MVCC mechanism in DuckDB, as well as its differences from databases like InnoDB and Oracle in terms of visibility checks and version number assignment.

In this MVCC implementation, there are three variables:

• transactionID

• startTime-stamps

• commitTime-stamps

When a transaction starts, the system assigns both a transactionID and a startTime-stamp.

• The transactionID is a very large value that increments starting from 2^63.

• The startTime-stamp increments starting from 0.

• The commitTime-stamp is assigned only at commit time, from the same incremental counter used for the startTime-stamp.

This design is similar to the relationship between trx_id and trx_no in InnoDB:

transactionID corresponds to InnoDB's trx_id. startTime-stamp and commitTime-stamp correspond to trx_no.

The difference lies in the fact that:

During a transaction, DuckDB records the transactionID in the UndoBuffer for every row modification. Since this transactionID is a very large value, only the current transaction can see it. When the transaction commits, DuckDB updates the timestamps of these versions in the UndoBuffer from the transactionID to the commitTime-stamp.

During a visibility check, because the transactionID is always larger than any startTime-stamp, uncommitted transactions are naturally not visible to other transactions, which makes the visibility check very simple.

v.pred = null ∨ v.pred.TS = T ∨ v.pred.TS < T.startTime

That is, for a transaction T:

• If a row has no older version,

• Or the row's version timestamp is equal to the current transaction's transactionID,

• Or the row's version timestamp is less than the current transaction's startTime-stamp,

then the row is visible to transaction T; otherwise, it is not.

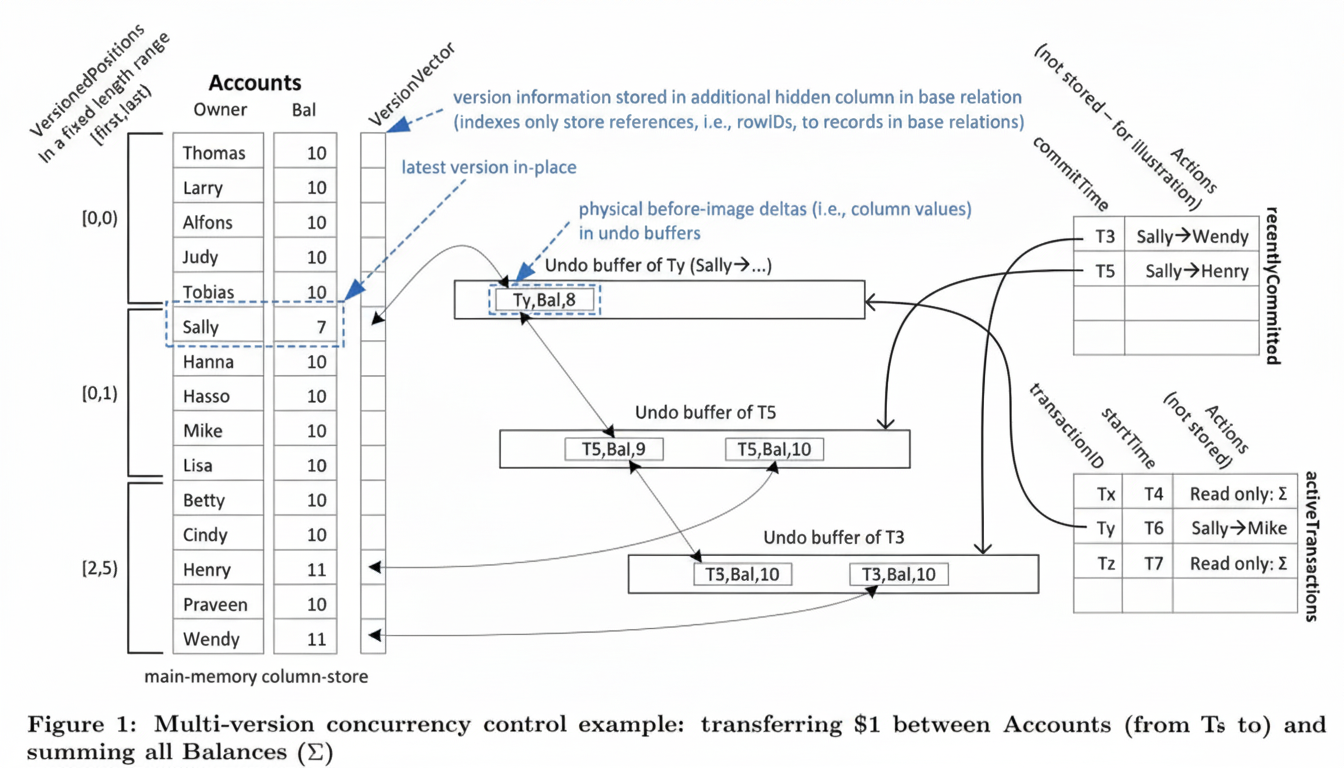

Let's use the following example.

Initially, everyone's balance is 10. Three transactions are initiated.

| Transaction | Operation | Status |

|---|---|---|

| trx1 | Starts at T3, transfers $1 from Sally to Wendy | Committed, in the recentlyCommitted transaction array |

| trx2 | Starts at T5, transfers $1 from Sally to Henry | Committed, in the recentlyCommitted transaction array |

| trx3 | Starts at T6, transfers $1 from Sally to Mike | Uncommitted, in the activeTransactions array |

| trx4 | Starts at T4, reads everyone's balance | startTime = T4, transactionID = Tx |

| trx5 | Starts at T7, reads everyone's balance again | starTtime = T7, transactionID = Tz |

(Note: Here, the UndoBuffer timestamp check refers to the visibility of the previous value. For example, the undo buffer of Ty corresponds to whether the value 7 is visible, and the undo buffer of T5 corresponds to whether the value 8 is visible.)

When trx4 reads at time T4, since its startTime = T4 > T3, it can see the changes committed by T3. The previous value from the undo buffer of T3 is Sally=9, Wendy=11. Other transactions have not yet started, so it can read the latest version directly.

The key point is trx3. Since trx3 has not yet committed, the first undo buffer entry pointed to by Sally records the Sally -> Mike operation, but it is still in progress; the Mike + 1 operation has not yet been executed. Because the transaction is uncommitted, the timestamp on this undo buffer is Ty, which is the transactionID of trx3 and is a very large value.

For instance, consider transaction trx5. Although its startTime = T7 is greater than trx3's startTime = T6, according to the visibility check formula below, the value 7 corresponding to the undo buffer of Ty is not visible to trx5. This is because trx5.transactionID != undo buffer of Ty and trx5.startTime < undo buffer of Ty. However, since the undo buffer of T5 < T7, the value 8 from that version is visible to trx5.

When checking transaction visibility, DuckDB does not use an active transaction array like InnoDB or PostgreSQL; it can make the determination directly using the start_time, similar to how Oracle's SCN implementation works.

How Does DuckDB Handle Visibility Checks Without an InnoDB-like read view?

In the existing InnoDB implementation, trx_id and trx_no are analogous to start_ts and end_ts.

The essence of visibility for a given row is to determine whether its content was already committed when the current transaction trx1 started.

In InnoDB, this is done by checking if the current transaction's trx_id is greater than the trx_no of the row being read.

However, the problem is that the row record itself contains the trx_id, not the trx_no.

So why does the row record only store the trx_id and not the trx_no as well?

Because doing so would incur a very high overhead.

InnoDB supports a steal and no-force policy, which means a record's corresponding page might be flushed to disk before the transaction commits. Therefore, when InnoDB writes the record, it doesn't know the trx_no yet. To implement this, it would need to obtain the trx_no during commit() (by executing trx_write_serialisation_history()) and then rewrite the trx_no back to the record.

If a transaction modifies 1000 rows, this would require rewriting the undo logs for all 1,000 rows at commit time, resulting in a massive overhead.

Because only the trx_id can be read from the row, InnoDB's visibility check does not use trx_no. Instead, it uses the transaction's starting trx_id and must combine it with an active transaction array, the read view, to determine visibility.

So, in fact, if the row record contained the trx_no, there would be no need for a read view; a direct comparison would suffice.

So how is the check performed?

The requirement remains the same: was the row being read already committed before trx1 started? The read view can tell us which transactions were still running when trx1 began; if a transaction was active, it was definitely not committed. Additionally, any transaction with a trx_id greater than the largest trx_id in the read view must also be uncommitted, because it wasn't even present when the read view was copied, meaning it surely hadn't committed by the time the current transaction started.

So how does Oracle circumvent this problem? And what are similar solutions?

A common optimization approach is to maintain a trx_id => trx_no mapping table, let's call it id_no_map. This reduces the overhead of writing the trx_no to every record at commit time by recording it in the id_no_map table instead.

The id_no_map can be purely in-memory or persistent. It can be in-memory because after a database restart, old trx_ids are visible to all new transactions. So, if a trx_id is smaller than the trx_id at MySQL startup, that transaction is definitely visible.

If the ID is larger than the startup trx_id and cannot be found in the id_no_map table, it is uncommitted; otherwise, its corresponding trx_no can be obtained.

Then, a transaction trx1.trx_id can be directly compared with a row it reads. If trx1.trx_id > id_no_map[row_trx_id], the row is visible to the transaction. If trx1.trx_id < id_no_map[row_trx_id], the row was committed after trx1 started, so it is not visible.

Of course, as trx_ids grow, the old trx_id => trx_no mappings must be cleaned up to avoid consuming too much memory.

In Oracle, this information is stored in the ITL (Interested Transaction List) slot within each page.

Key information: Each ITL slot typically contains:

• Transaction ID (XID): Uniquely identifies a transaction.

• Commit SCN (System Change Number): When the transaction commits, this slot is updated with the transaction's commit SCN. If the transaction is uncommitted or rolled back, this value is usually NULL or a special value (e.g., 0x0000.00000000).

So, when reading a row within a page, after retrieving the row's XID, the system will use the ITL on that page to map the XID to an SCN. Because the ITL is at the page level, not the record level, the overhead of modifying 1000 records is reduced to just one page modification.

DuckDB's implementation is further simplified. It has two advantages that make its implementation very simple.

Rebuild Search Pipelines: An Analysis of PolarDB IMCI Capabilities

PolarDB-X v2.4.2: Upgrades to Open-Source Ecosystem Integration

ApsaraDB - February 5, 2026

ApsaraDB - November 26, 2025

ApsaraDB - February 5, 2026

ApsaraDB - September 10, 2025

ApsaraDB - November 13, 2025

ApsaraDB - November 18, 2025

Database for FinTech Solution

Database for FinTech Solution

Leverage cloud-native database solutions dedicated for FinTech.

Learn More Oracle Database Migration Solution

Oracle Database Migration Solution

Migrate your legacy Oracle databases to Alibaba Cloud to save on long-term costs and take advantage of improved scalability, reliability, robust security, high performance, and cloud-native features.

Learn More Database Migration Solution

Database Migration Solution

Migrating to fully managed cloud databases brings a host of benefits including scalability, reliability, and cost efficiency.

Learn More DBStack

DBStack

DBStack is an all-in-one database management platform provided by Alibaba Cloud.

Learn MoreMore Posts by ApsaraDB