By Zhang Xizhe and Chen Zongzhi

For any database, the transaction system is a crucial component. When we talk about transactions, the four ACID properties are what immediately come to mind. DuckDB has implemented these four fundamental properties in its own way:

• A (Atomicity): Requires that all operations within a transaction either succeed completely or are rolled back. In DuckDB, this property is achieved through the WAL (Write-Ahead Log), Undo Buffer, and Local Storage.

• C (Consistency): Requires that a transaction does not violate constraints (such as unique keys, foreign keys, etc.) before and after its execution. For example, in DuckDB, the uniqueness of unique keys is maintained by the ART index.

• I (Isolation): Each transaction should operate as if it were running exclusively, unaffected by the intermediate results of other uncommitted transactions. In DuckDB, the MVCC mechanism is implemented using the Undo Buffer and Local Storage to achieve snapshot isolation.

• D (Durability): Once a transaction is committed, its results will not be lost due to crashes, power outages, or restarts. In DuckDB, this property is achieved using the WAL.

As you can see, the transaction system is a rather large module. This article will focus on the start, commit, and rollback of a transaction from the perspective of its lifecycle. Subsequent articles will analyze other parts one by one. This article is based on the source code of DuckDB version 1.3.1. See the end of the article for a TL;DR.

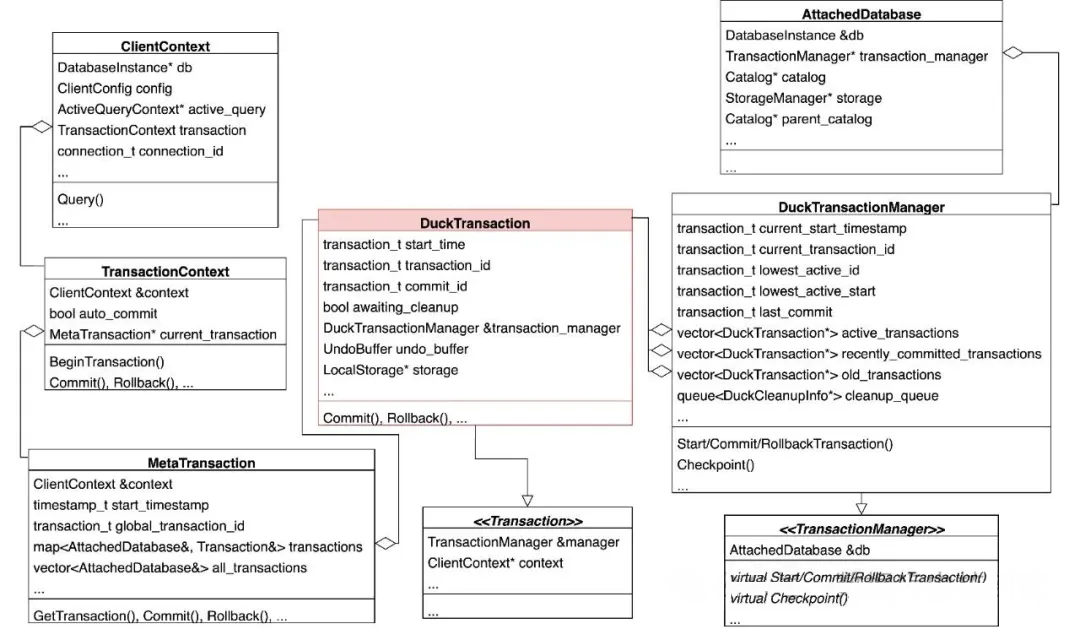

The UML diagram above provides an overview of the classes related to transactions. The highlighted DuckTransaction class represents an actual transaction. Let's examine this diagram from left to right and then from right to left:

• From left to right:

ClientContext class represents a session (similar to a THD object in MySQL) and contains a TransactionContext object.TransactionContext class represents the transaction state of the current session, such as the auto_commit variable, which indicates whether the session is in single-statement or multi-statement transaction mode. Another important member of this class is a MetaTransaction object.MetaTransaction class maintains a map from AttachedDatabase to DuckTransaction. It's worth noting here that each AttachedDatabase object actually represents a database (comparable to different storage engines in MySQL). Under normal circumstances, there are only three: system and temp, which are built-in in-memory databases, and one user database that has a physical file. In DuckDB, you can load more user databases using the ATTACH command. Each AttachedDatabase in DuckDB maintains its own transaction management system and has its own WAL. The MetaTransaction acts more like a distributed transaction (analogous to a SQL-layer transaction in MySQL that coordinates various participating storage engines), corresponding to several sub-transactions (usually just the three: system, temp, and the user database), which are DuckTransactions. However, since DuckDB does not currently support the 2PC protocol, it does not guarantee atomicity for transactions across AttachedDatabases, serving more of a symbolic role.DuckTransaction class represents a transaction within a single database (analogous to an InnoDB-layer transaction in MySQL, which is only concerned with the InnoDB storage engine itself). This transaction satisfies the ACID properties mentioned earlier.• From right to left:

AttachedDatabase class represents a database file. It contains a DuckTransactionManager object, which is responsible for managing transactions within this database.DuckTransactionManager class has many important member variables. For example, when a transaction starts, it acquires auto-incrementing current_start_timestamp and current_transaction_id values, which are closely related to visibility checks in MVCC. This class also maintains the active_transactions, recently_committed_transactions, and old_transactions arrays, which contain DuckTransaction class pointers, managing the lifecycle of a transaction from a global perspective.Similar to MySQL, by default in DuckDB, a single SQL statement executes as its own single-statement transaction. Multiple SQL statements wrapped in BEGIN and COMMIT/ROLLBACK form a multi-statement transaction. To distinguish between these two modes, DuckDB uses the session's auto_commit variable (located in the TransactionContext class) to determine if the current session is in a multi-statement transaction:

• true: The session is in single-statement transaction mode or not in any transaction.

• false: The session is in a multi-statement transaction.

Let's first look at how a single SQL statement starts and commits (or rolls back) a transaction without an explicit BEGIN. The following example uses the ClientContext::Query API to show a typical call stack related to transactions:

ClientContext::Query

├── ClientContext::PendingQueryInternal

│ └── ClientContext::PendingStatementOrPreparedStatementInternal

│ └── ClientContext::PendingStatementOrPreparedStatement

│ └── ClientContext::BeginQueryInternal

│ └── TransactionContext::BeginTransaction

└── ClientContext::ExecutePendingQueryInternal

└── PendingQueryResult::ExecuteInternal

└── ClientContext::FetchResultInternal

└── ClientContext::CleanupInternal

└── ClientContext::EndQueryInternal

└── TransactionContext::Commit or TransactionContext::RollbackFrom the call stack, we can see that DuckDB calls ClientContext::BeginQueryInternal and ClientContext::EndQueryInternal before and after executing an SQL statement, respectively. The logic of these two functions is quite simple, as shown below:

void ClientContext::BeginQueryInternal(ClientContextLock &lock, const string &query){

...

if (transaction.IsAutoCommit()) {

/* If auto_commit=1 (indicating single-statement transaction mode), create a MetaTransaction object and assign an instance-level, auto-incrementing global_transaction_id. */

transaction.BeginTransaction();

}

/* Assign an instance-level, auto-incrementing Query ID to the current query and set it on the newly created MetaTransaction object. This Query ID will be used later to determine if a transaction object can be cleaned up. */

transaction.SetActiveQuery(db->GetDatabaseManager().GetNewQueryNumber());

...

}

ErrorData ClientContext::EndQueryInternal(ClientContextLock &lock, bool success, bool invalidate_transaction,

optional_ptr<ErrorData> previous_error){

...

if (transaction.HasActiveTransaction()) {

transaction.ResetActiveQuery();

if (transaction.IsAutoCommit()) {

/* In single-statement transaction mode, commit or roll back based on execution success. */

if (success) {

transaction.Commit();

} else {

transaction.Rollback(previous_error);

}

} else if (invalidate_transaction) {

/* In multi-statement mode, if a statement fails and causes the entire transaction to be invalidated, the transaction is marked as invalid, and only ROLLBACK is allowed afterward. */

ValidChecker::Invalidate(ActiveTransaction(), "Failed to commit");

}

}

...

}The three statements related to multi-statement transactions - BEGIN, COMMIT, and ROLLBACK - are all executed by the PhysicalTransaction physical operator. Therefore, the entry point for all three is PhysicalTransaction::GetData, with the following call stack:

PhysicalTransaction::GetData

├── TransactionContext::SetAutoCommit // Starts a multi-statement transaction

│ └── (optional) TransactionContext::BeginTransaction

├── (optional) MetaTransaction::GetTransaction

│ └── DuckTransactionManager::StartTransaction

├── TransactionContext::Commit // Commits a multi-statement transaction

│ └── MetaTransaction::Commit

│ └── DuckTransactionManager::CommitTransaction

└── TransactionContext::Rollback // Rolls back a multi-statement transaction

└── MetaTransaction::Rollback

└── DuckTransactionManager::RollbackTransactionBefore introducing the PhysicalTransaction::GetData function, it's necessary to explain how the immediate_transaction_mode parameter affects the behavior of the BEGIN statement:

• false (default setting): When BEGIN is executed, it only sets the auto_commit variable to false, marking the start of a multi-statement transaction mode (similar to MySQL's behavior). The actual DuckTransaction object is created lazily during subsequent execution.

• true: When BEGIN is executed, a DuckTransaction must be created for every AttachedDatabase, effectively starting a transaction immediately in each one.

Now let's look at the implementation of the PhysicalTransaction::GetData function. You can see that COMMIT and ROLLBACK call the same functions as in single-statement mode, just from a different call site. The main difference lies in how BEGIN is handled:

SourceResultType PhysicalTransaction::GetData(ExecutionContext &context, DataChunk &chunk,

OperatorSourceInput &input) const{

auto &client = context.client;

auto type = info->type;

if (type == TransactionType::COMMIT && ValidChecker::IsInvalidated(client.ActiveTransaction())) {

/* If a transaction has already been invalidated, a COMMIT will be converted to a ROLLBACK. */

type = TransactionType::ROLLBACK;

}

/* Execute different logic for BEGIN, COMMIT, and ROLLBACK. */

switch (type) {

case TransactionType::BEGIN_TRANSACTION: { /* BEGIN */

if (client.transaction.IsAutoCommit()) {

/* Set auto_commit to false to indicate multi-statement transaction mode. */

client.transaction.SetAutoCommit(false);

auto &config = DBConfig::GetConfig(context.client);

if (info->modifier == TransactionModifierType::TRANSACTION_READ_ONLY) {

/* Mark the transaction as read-only if specified. */

client.transaction.SetReadOnly();

}

if (config.options.immediate_transaction_mode) {

/* If immediate_transaction_mode is enabled, a DuckTransaction must be created for all `AttachedDatabase` operations. This is inefficient and not the default behavior. */

auto databases = DatabaseManager::Get(client).GetDatabases(client);

for (auto db : databases) {

context.client.transaction.ActiveTransaction().GetTransaction(db.get());

}

}

} else {

throw TransactionException("cannot start a transaction within a transaction");

}

break;

}

case TransactionType::COMMIT: { /* COMMIT */

if (client.transaction.IsAutoCommit()) {

throw TransactionException("cannot commit - no transaction is active");

} else {

/* Calls DuckTransactionManager::CommitTransaction for each participating DuckTransaction. */

client.transaction.Commit();

}

break;

}

case TransactionType::ROLLBACK: { /* ROLLBACK */

if (client.transaction.IsAutoCommit()) {

throw TransactionException("cannot rollback - no transaction is active");

} else {

/* Calls DuckTransactionManager::RollbackTransaction for each participating DuckTransaction. */

auto &valid_checker = ValidChecker::Get(client.transaction.ActiveTransaction());

if (valid_checker.IsInvalidated()) {

ErrorData error(ExceptionType::TRANSACTION, valid_checker.InvalidatedMessage());

client.transaction.Rollback(error);

} else {

client.transaction.Rollback(nullptr);

}

}

break;

}

default:

throw NotImplementedException("Unrecognized transaction type!");

}

return SourceResultType::FINISHED;

}As mentioned earlier, under the default configuration, the BEGIN statement merely flags a state and does not actually start a DuckTransaction. A transaction is truly started during the Bind phase of SQL parsing. At this point, it is known exactly which AttachedDatabase is involved in the transaction. If it has not yet started a transaction, a DuckTransaction object is constructed for it, truly starting the transaction.

Typically, system, temp, and the user database will start transactions during the Bind process. The first two are purely in-memory, so there's no need to worry about persistence. The typical call stack for starting a transaction in a user database is shown below. It is quite deep, presented here just to show the call site. Content related to managing Catalog Entries will be covered in future articles.

Binder::Bind

└── CatalogEntryRetriever::GetEntry

└── Catalog::GetEntry

└── Catalog::TryLookupEntry(CatalogEntryRetriever &retriever, const string &catalog, ...)

└── Catalog::TryLookupEntry(CatalogEntryRetriever &retriever, const vector<CatalogLookup> &lookups, ...)

└── Catalog::GetCatalogTransaction

└── CatalogTransaction::CatalogTransaction

└── Transaction::Get(ClientContext &context, Catalog &catalog)

└── Transaction::Get(ClientContext &context, AttachedDatabase &db)

└── MetaTransaction::GetTransaction

└── DuckTransactionManager::StartTransactionLet's look at the implementation of DuckTransactionManager::StartTransaction:

Transaction &DuckTransactionManager::StartTransaction(ClientContext &context) {

auto &meta_transaction = MetaTransaction::Get(context);

unique_ptr<lock_guard<mutex>> start_lock;

if (!meta_transaction.IsReadOnly()) {

/* 1. 1. Non-read-only transactions need to acquire start_transaction_lock, preventing new transactions from starting during a FORCE CHECKPOINT. */

start_lock = make_uniq<lock_guard<mutex>>(start_transaction_lock);

}

/* 2. Acquire transaction_lock to make BEGIN, COMMIT, and ROLLBACK mutually exclusive among transactions. */

lock_guard<mutex> lock(transaction_lock);

/* 3. Assign a start timestamp using the auto-incrementing current_start_timestamp (starts from 2). */

transaction_t start_time = current_start_timestamp++;

/* 4. Assign a transaction ID using the auto-incrementing current_transaction_id (starts from 2^62+96). */

transaction_t transaction_id = current_transaction_id++;

if (active_transactions.empty()) {

/* 5. If there are no active transactions, record this transaction's start timestamp and transaction ID in lowest_active_start/id. */

lowest_active_start = start_time;

lowest_active_id = transaction_id;

}

/* 6. Construct a DuckTransaction object and add it to the active_transactions array for management. */

auto transaction = make_uniq<DuckTransaction>(*this, context, start_time, transaction_id, last_committed_version);

auto &transaction_ref = *transaction;

active_transactions.push_back(std::move(transaction));

return transaction_ref;

}After a DuckTransaction is started, its is_read_only variable is initialized to true (Note: The original text says false, but a fresh transaction starts as read-only. The purpose of SetReadWrite is to change this state. Let's assume the author meant it's marked as read-write later). The transaction is only marked as a read-write transaction when a write operation actually occurs. Read-write transactions have more complex handling during commit compared to read-only transactions. Below is a typical call stack for marking a transaction as read-write. This can be determined after an SQL statement has been parsed, revealing whether it will cause a write operation. The final call is to DuckTransaction::SetReadWrite.

ClientContext::Query

└── ClientContext::PendingQueryInternal

└── ClientContext::PendingStatementOrPreparedStatementInternal

└── ClientContext::PendingStatementOrPreparedStatement

└── ClientContext::PendingStatementInternal

└── ClientContext::CheckIfPreparedStatementIsExecutable

└── MetaTransaction::ModifyDatabase

└── DuckTransaction::SetReadWriteAs shown below, the implementation of DuckTransaction::SetReadWrite is straightforward: it sets is_read_only to false and acquires a shared lock on checkpoint_lock, a coarse-grained lock that blocks Checkpoints for the duration of the transaction.

void DuckTransaction::SetReadWrite() {

/* Set is_read_only to false. */

Transaction::SetReadWrite();

/* Acquire a shared lock on checkpoint_lock, which blocks Checkpoints for the duration of the transaction. */

write_lock = transaction_manager.SharedCheckpointLock();

}Committing a transaction is the most complex part of its lifecycle. This article will focus on the main flow of the commit process, briefly touching upon the details of LocalStorage, UndoBuffer, and the WAL, which will be detailed in future articles. The call stack is as follows:

DuckTransactionManager::CommitTransaction

├── DuckTransaction::WriteToWAL // In most cases that don't trigger a Checkpoint, writes to the WAL, mutually exclusive with step 6.

│ ├── LocalStorage::Commit

│ │ └── LocalStorage::Flush // 1. Merge this transaction's insertions into the table.

│ └── UndoBuffer::WriteToWAL

│ └── WALWriteState::CommitEntry // 2. Write to the WAL (on-disk state).

├── DuckTransaction::Commit

│ ├── (optional) LocalStorage::Commit // Mostly done in step 1, this is a fallback for cases that trigger a Checkpoint and don't write to the WAL.

│ └── UndoBuffer::Commit

│ └── CommitState::CommitEntry // 3. Update the visibility of modifications made by this transaction (in-memory state).

├── DuckTransactionManager::RemoveTransaction // 4. Collect transaction objects that can be cleaned up.

├── DuckCleanupInfo::Cleanup

│ └── DuckTransaction::Cleanup

│ └── UndoBuffer::Cleanup // 5. Clean up transaction objects that are no longer needed (by MVCC).

└── (optional) SingleFileStorageManager::CreateCheckpoint

└── SingleFileCheckpointWriter::CreateCheckpoint // 6. Trigger a Checkpoint based on certain conditions (on-disk state).As you can see, besides steps 1, 2, and 3, which are related to the current transaction's commit, the commit process may also perform cleanup and checkpointing tasks. This is quite different from more mature transaction engines like InnoDB, where these tasks are handled by background threads asynchronously (e.g., the Undo Purge thread for steps 4 and 5, and the Buffer Pool I/O and Redo Checkpointer threads for step 6). Therefore, DuckDB's foreground user threads may experience unstable latency caused by steps 4, 5, and 6. There is indeed a lot of room for optimization here.

Now let's examine the implementation of DuckTransactionManager::CommitTransaction:

1. Acquire the transaction_lock, which blocks the start, commit, and rollback of other transactions.

2. Check if this commit should trigger a checkpoint. The details of this check will be discussed later. If a checkpoint is decided, it will attempt to upgrade the checkpoint_lock to an exclusive lock, which is a coarse-grained lock that blocks other sessions from performing write operations or checkpoints.

3. If no checkpoint is performed this time, the modifications made by this transaction need to be written to the WAL. This involves several steps:

LocalStorage::Commit to merge the data inserted by this transaction into the table (in-memory state), followed by UndoBuffer::WriteToWAL to actually write to the WAL (on-disk state).4. Assign a Commit ID to the transaction using the auto-incrementing current_start_timestamp variable (starting from 2). This is the same auto-incrementing variable used when starting the transaction. During MVCC, visibility can be determined based on start_time and the data's commit_id.

5. Call UndoBuffer::Commit to mark the modifications made by this transaction with the just-assigned Commit ID. Transactions starting after this point will be able to see these changes.

6. If it was decided not to checkpoint in step 2, the checkpoint_lock held by this transaction can be released (read-write transactions hold a shared lock, read-only transactions hold none).

7. If the current transaction "contains Update operations," "contains Delete operations involving a secondary index," or "contains DDL," then the transaction object cannot be destroyed immediately because its Undo Buffer is still needed for MVCC. In DuckTransactionManager::RemoveTransaction, the state of all transaction objects is transitioned, and all cleanable transaction objects are identified and returned (this logic will be detailed later). The returned cleanup_info is then added to the cleanup_queue under the protection of cleanup_queue_lock.

SingleFileCheckpointWriter::CreateCheckpoint (as introduced in the previous article on file formats).ErrorData DuckTransactionManager::CommitTransaction(ClientContext &context, Transaction &transaction_p){

auto &transaction = transaction_p.Cast<DuckTransaction>();

/* 1. Acquire the transaction_lock. */

unique_lock<mutex> t_lock(transaction_lock);

...

/* 2. Check if this commit should trigger a Checkpoint. */

unique_ptr<StorageLockKey> lock;

auto undo_properties = transaction.GetUndoProperties();

auto checkpoint_decision = CanCheckpoint(transaction, lock, undo_properties);

unique_ptr<lock_guard<mutex>> held_wal_lock;

unique_ptr<StorageCommitState> commit_state;

/* 3. If not checkpointing, write this transaction's modifications to the WAL. */

if (!checkpoint_decision.can_checkpoint && transaction.ShouldWriteToWAL(db)) {

/* 3.i Release transaction_lock, a small optimization. */

t_lock.unlock();

/* 3.ii Acquire wal_lock to serialize WAL writes for concurrent commits. */

held_wal_lock = make_uniq<lock_guard<mutex>>(wal_lock);

/* 3.iii Internally calls LocalStorage::Commit to merge inserted data (in-memory), then UndoBuffer::WriteToWAL to write the WAL (on-disk). */

error = transaction.WriteToWAL(db, commit_state);

/* 3.iv Re-acquire transaction_lock after writing to the WAL. */

t_lock.lock();

}

/* 4. Assign a Commit ID using the auto-incrementing current_start_timestamp (starts from 2). */

transaction_t commit_id = GetCommitTimestamp();

/* 5. Call UndoBuffer::Commit to mark modifications with the new Commit ID, making them visible to subsequent transactions. */

transaction.Commit(db, commit_id, std::move(commit_state));

... /* Error handling */

/* If this transaction performed DDL, increment last_committed_version. */

if (transaction.catalog_version >= TRANSACTION_ID_START) {

transaction.catalog_version = ++last_committed_version;

}

OnCommitCheckpointDecision(checkpoint_decision, transaction); /* Empty function*/

if (!checkpoint_decision.can_checkpoint && lock) {

/* 6. If not checkpointing (step 2), release the held checkpoint_lock (read-write TXs hold an S-lock, read-only TXs hold none). */

lock.reset();

}

/* If the current transaction "contains Updates," "contains Deletes on an indexed table," or "contains DDL," it cannot be destroyed immediately as it's needed for MVCC. This is passed to RemoveTransaction. */

bool store_transaction = undo_properties.has_updates || undo_properties.has_index_deletes ||

undo_properties.has_catalog_changes || error.HasError();

/* 7. Transition the state of all transaction objects, find those ready for cleanup, and add the resulting cleanup_info to the cleanup_queue under cleanup_queue_lock. */

auto cleanup_info = RemoveTransaction(transaction, store_transaction);

if (cleanup_info->ScheduleCleanup()) {

lock_guard<mutex> q_lock(cleanup_queue_lock);

cleanup_queue.emplace(std::move(cleanup_info));

}

/* 8. Release the transaction_lock. */

t_lock.unlock();

{

/* 9. Under the protection of cleanup_lock, clean up unneeded transaction objects. */

lock_guard<mutex> c_lock(cleanup_lock);

unique_ptr<DuckCleanupInfo> top_cleanup_info;

{

lock_guard<mutex> q_lock(cleanup_queue_lock);

/* Under the protection of cleanup_queue_lock, retrieve the first cleanup_info from the queue. */

if (!cleanup_queue.empty()) {

top_cleanup_info = std::move(cleanup_queue.front());

cleanup_queue.pop();

}

}

if (top_cleanup_info) {

/* Clean up all transaction objects within the retrieved cleanup_info. */

top_cleanup_info->Cleanup();

}

}

/* 10. If a checkpoint was decided in step 2, perform a checkpoint on the entire database. */

if (checkpoint_decision.can_checkpoint) {

CheckpointOptions options;

options.action = CheckpointAction::ALWAYS_CHECKPOINT;

options.type = checkpoint_decision.type;

auto &storage_manager = db.GetStorageManager();

storage_manager.CreateCheckpoint(context, options);

}

return error;

}As mentioned earlier, DuckDB decides at the beginning of a transaction commit whether to perform a checkpoint. Next, we will detail the conditions for triggering a checkpoint. The relevant call stack is:

DuckTransactionManager::CommitTransaction

├── DuckTransaction::GetUndoProperties

│ └── UndoBuffer::GetProperties

└── DuckTransactionManager::CanCheckpointThe process is divided into three parts:

• The UndoBuffer::GetProperties function determines the specific modifications made by the transaction and estimates the size of the WAL that these modifications will generate. Here is an explanation of the fields in the returned UndoBufferProperties object:

has_updates: The transaction contains UPDATE operations.has_deletes: The transaction contains DELETE operations.has_index_deletes: The transaction contains DELETE operations and there is a secondary index.has_catalog_changes: The transaction contains DDL operations.has_dropped_entries: The transaction's DDL includes a DROP action.estimated_size: The estimated size of the WAL to be written by the transaction.• The DuckTransactionManager::CanCheckpoint function determines whether the current commit should trigger a checkpoint, based on the following conditions:

AttachedDatabase is not the system database or an in-memory-only database.checkpoint_threshold parameter (alias wal_autocheckpoint, variable named checkpoint_wal_size in the code, default 16MB).has_updates or has_dropped_entries, and there are other active transactions (which must be read-only), a checkpoint cannot be performed for MVCC reasons.• After satisfying the above checkpoint conditions, DuckTransactionManager::CanCheckpoint will also determine whether to perform a FULL_CHECKPOINT or a CONCURRENT_CHECKPOINT (this mode cannot clean up deleted data because it might still be in use by MVCC). A CONCURRENT_CHECKPOINT is used in only one scenario:

has_deletes, and there are other active transactions (which must be read-only), the deleted data cannot be cleaned up for MVCC considerations.From the commit process described earlier, we know that committing a transaction is also responsible for cleaning up previously committed transactions. This is because after a transaction is committed or rolled back, the DuckTransaction object is often not immediately destroyed, as its Undo Buffer is still used for MVCC. A transaction object is only truly cleaned up when it is certain that it can no longer be used by any currently active transactions. The call stack related to transaction state transition and cleanup is as follows:

DuckTransactionManager::CommitTransaction

├── DuckTransactionManager::RemoveTransaction

└── DuckCleanupInfo::Cleanup

└── DuckTransaction::Cleanup

└── UndoBuffer::CleanupThe process can be seen in two parts:

• DuckTransactionManager::RemoveTransaction checks which committed transactions can be cleaned up and collects them. This section will be the focus of our discussion.

• DuckCleanupInfo::Cleanup calls down to UndoBuffer::Cleanup to perform the final cleanup work on the Undo Entries in the Undo Buffer, categorized by type. The logic of this part will be introduced in a future article.

To transition DuckTransaction objects between different states, DuckTransactionManager maintains three arrays and one queue:

• active_transactions: Contains all active transactions. When a transaction commits, if it meets the following conditions (essentially the calculation for the store_transaction parameter), it is moved to recently_committed_transactions; otherwise, it is added directly to a DuckCleanupInfo object to await cleanup:

has_updates || has_index_deletes || has_catalog_changes, which means the contents of this transaction's Undo Buffer might still be used (e.g., for MVCC).• recently_committed_transactions: Contains committed transactions that are still in use by MVCC. They can be checked by their commit_id to see if they are no longer needed. If so, they are moved to the old_transactions array.

• old_transactions: Contains transactions no longer used by MVCC, but whose UpdateInfo might still be in use by active queries (a historical reason, no longer necessary as of v1.4.0; the author's PR #19381 to remove this array has been merged into the official main branch). They can be checked by their highest_active_query variable to see if they are no longer needed. If so, they are added to a DuckCleanupInfo object to await cleanup.

• cleanup_queue: Contains pointers to DuckCleanupInfo objects. Each DuckCleanupInfo object has a transactions array, and the transaction objects inside are all ready to be cleaned up.

Let's look at the implementation of DuckTransactionManager::RemoveTransaction:

1. Iterate through the active_transactions array to find the lowest start timestamp (start_time), transaction ID, and Query ID among all active transactions.

2. Decide which array to move the current transaction to:

3. Iterate through the recently_committed_transactions array to find all transactions whose commit time (Commit ID) is earlier than the start time (start_time) of any currently active transaction. This means these transactions are no longer needed for MVCC. However, their UpdateInfo might still be in use by currently active queries (historical reason, this part of the logic was removed in PR #19381), so the current_query (the current highest Query ID) is recorded in highest_active_query. They are then moved to the old_transactions array, to be truly cleaned up (destroying the transaction object and its Undo Buffer) only after all currently active queries have finished.

4. Iterate through the old_transactions array to find all transaction objects that are completely unused, i.e., the IDs of all currently active queries are greater than the transaction's highest_active_query. Add these transactions to cleanup_info to await cleanup.

unique_ptr<DuckCleanupInfo> DuckTransactionManager::RemoveTransaction(DuckTransaction &transaction,

bool store_transaction) noexcept{

auto cleanup_info = make_uniq<DuckCleanupInfo>();

idx_t t_index = active_transactions.size();

auto lowest_start_time = TRANSACTION_ID_START;

auto lowest_transaction_id = MAX_TRANSACTION_ID;

auto lowest_active_query = MAXIMUM_QUERY_ID;

/* 1. Iterate through active_transactions to find the lowest start_time, transaction_id, and query_id. */

for (idx_t i = 0; i < active_transactions.size(); i++) {

if (active_transactions[i].get() == &transaction) {

/* Locate the index of the current transaction. */

t_index = i;

continue;

}

lowest_start_time = MinValue(lowest_start_time, active_transactions[i]->start_time);

lowest_transaction_id = MinValue(lowest_transaction_id, active_transactions[i]->transaction_id);

transaction_t active_query = active_transactions[i]->active_query;

lowest_active_query = MinValue(lowest_active_query, active_query);

}

lowest_active_start = lowest_start_time;

lowest_active_id = lowest_transaction_id;

auto current_transaction = std::move(active_transactions[t_index]);

auto current_query = DatabaseManager::Get(db).ActiveQueryNumber();

/* 2. Decide which array to move the current transaction to. */

if (store_transaction) {

/* The current transaction is needed for MVCC. */

if (transaction.commit_id != 0) {

/* 2.i The transaction was successfully committed, move to recently_committed_transactions. */

recently_committed_transactions.push_back(std::move(current_transaction));

} else {

/* 2.ii The transaction was not successfully committed, move to old_transactions. */

current_transaction->highest_active_query = current_query;

old_transactions.push_back(std::move(current_transaction));

}

} else if (transaction.ChangesMade()) {

/* 2.iii The transaction does not need to be kept, add directly to cleanup_info for cleanup. */

current_transaction->awaiting_cleanup = true;

cleanup_info->transactions.push_back(std::move(current_transaction));

}

cleanup_info->lowest_start_time = lowest_start_time;

/* Remove the current transaction from the active_transactions array. */

active_transactions.unsafe_erase_at(t_index);

/* 33. Iterate recently_committed_transactions to find transactions with commit_id < lowest_start_time. They are no longer needed for MVCC. However, their UpdateInfo might still be used by active queries, so record current_query in highest_active_query. They can be destroyed after these queries finish. */

idx_t i = 0;

for (; i < recently_committed_transactions.size(); i++) {

if (recently_committed_transactions[i]->commit_id >= lowest_start_time) {

/* The commit_ids in the array are incremental, so we can break directly. */

break;

}

recently_committed_transactions[i]->awaiting_cleanup = true;

recently_committed_transactions[i]->highest_active_query = current_query;

old_transactions.push_back(std::move(recently_committed_transactions[i]));

}

if (i > 0) {

/* Clean up these transaction objects from the recently_committed_transactions array. */

auto start = recently_committed_transactions.begin();

auto end = recently_committed_transactions.begin() + static_cast<int64_t>(i);

recently_committed_transactions.erase(start, end);

}

/* 4. Iterate old_transactions to find completely unused objects, i.e., all active query IDs are greater than the transaction's highest_active_query. */

i = active_transactions.empty() ? old_transactions.size() : 0;

for (; i < old_transactions.size(); i++) {

if (old_transactions[i]->highest_active_query >= lowest_active_query) {

/* The highest_active_query in the array is also incremental, so we can break. */

break;

}

}

if (i > 0) {

/* Move these transactions from old_transactions to cleanup_info for cleanup. */

for (idx_t t_idx = 0; t_idx < i; t_idx++) {

cleanup_info->transactions.push_back(std::move(old_transactions[t_idx]));

}

old_transactions.erase(old_transactions.begin(), old_transactions.begin() + static_cast<int64_t>(i));

}

return cleanup_info;

}The logic for rolling back a transaction is much simpler. As seen from the call stack below, it is divided into two parts: transaction rollback and transaction cleanup. The transaction rollback itself includes rollbacks for LocalStorage and UndoBuffer, which will be covered in future articles and are not the focus here. The transaction cleanup logic is the same as that described in the commit process.

DuckTransactionManager::RollbackTransaction

├── DuckTransaction::Rollback

│ ├── LocalStorage::Rollback

│ └── UndoBuffer::Rollback

├── DuckTransactionManager::RemoveTransaction

└── DuckCleanupInfo::CleanupThe implementation of DuckTransactionManager::RollbackTransaction is quite simple:

DuckTransactionManager::RemoveTransaction, which transitions the state of all transaction objects and identifies those that can be cleaned up, returning them (as described earlier). The returned cleanup_info is then added to the cleanup_queue under the protection of cleanup_queue_lock.void DuckTransactionManager::RollbackTransaction(Transaction &transaction_p){

...

{

/* 1. Acquire the transaction_lock. */

lock_guard<mutex> t_lock(transaction_lock);

error = transaction.Rollback();

/* 2. Transition the state of all transaction objects and find those ready for cleanup. */

auto cleanup_info = RemoveTransaction(transaction);

if (cleanup_info->ScheduleCleanup()) {

/* Add the returned cleanup_info to the cleanup_queue under cleanup_queue_lock. */

lock_guard<mutex> q_lock(cleanup_queue_lock);

cleanup_queue.emplace(std::move(cleanup_info));

}

}

{

/* 3. Under the protection of cleanup_lock and cleanup_queue_lock, retrieve the first cleanup_info from the queue and clean up all transaction objects within it. */

lock_guard<mutex> c_lock(cleanup_lock);

unique_ptr<DuckCleanupInfo> top_cleanup_info;

{

lock_guard<mutex> q_lock(cleanup_queue_lock);

if (!cleanup_queue.empty()) {

top_cleanup_info = std::move(cleanup_queue.front());

cleanup_queue.pop();

}

}

if (top_cleanup_info) {

top_cleanup_info->Cleanup();

}

}

...

}• Similar to MySQL, every transaction in DuckDB can be seen as an internal distributed transaction (MetaTransaction class, corresponding to MySQL's SQL-layer transaction), which contains transactions within multiple AttachedDatabases (DuckTransaction class, corresponding to MySQL's InnoDB-layer transaction). In regular usage, all tables are in a single DuckDB file, so the participants are only the system, temp, and user database AttachedDatabases. The first two are purely in-memory, so we only need to focus on the latter.

• Because DuckDB does not implement 2PC (Two-Phase Commit), a MetaTransaction involving multiple files does not guarantee atomicity. However, in the common case of a single DuckDB file, because DuckTransaction itself guarantees the four ACID properties, transactions within a single file behave as expected.

• Similar to MySQL, by default in DuckDB, a single SQL statement executes as its own single-statement transaction. Multiple SQL statements wrapped in BEGIN and COMMIT/ROLLBACK form a multi-statement transaction. To distinguish between these two modes, DuckDB uses the session's auto_commit variable (located in the TransactionContext class):

• By default, the BEGIN statement only sets the auto_commit flag and does not actually create a DuckTransaction object. A DuckTransaction is created lazily for the involved AttachedDatabases only when a subsequent SQL statement is executed. This behavior is controlled by the immediate_transaction_mode parameter.

• When committing a transaction, DuckDB may also perform cleanup of committed transactions and checkpointing. This is quite different from more mature transaction engines like InnoDB, where these tasks are handled by background threads asynchronously. This can cause DuckDB's foreground user threads to experience unstable latency.

• The locking granularity in DuckDB's transaction system is coarse. BEGIN, COMMIT, and ROLLBACK are mutually blocking, and checkpoints block write transactions. There is significant room for optimization here.

This article has primarily focused on the lifecycle of a transaction, with an emphasis on basic concepts and the handling of BEGIN, COMMIT, and ROLLBACK. We have not delved into Local Storage, Undo Buffer, or the WAL. These important modules will be detailed one by one in future articles, so stay tuned.

ApsaraDB - February 5, 2026

ApsaraDB - November 13, 2025

ApsaraDB - September 3, 2025

ApsaraDB - November 18, 2025

ApsaraDB - January 28, 2026

ApsaraDB - November 12, 2025

SOFAStack™

SOFAStack™

A one-stop, cloud-native platform that allows financial enterprises to develop and maintain highly available applications that use a distributed architecture.

Learn More Database for FinTech Solution

Database for FinTech Solution

Leverage cloud-native database solutions dedicated for FinTech.

Learn More Oracle Database Migration Solution

Oracle Database Migration Solution

Migrate your legacy Oracle databases to Alibaba Cloud to save on long-term costs and take advantage of improved scalability, reliability, robust security, high performance, and cloud-native features.

Learn More Database Migration Solution

Database Migration Solution

Migrating to fully managed cloud databases brings a host of benefits including scalability, reliability, and cost efficiency.

Learn MoreMore Posts by ApsaraDB