DuckDB features one of the more advanced optimizers among OLAP databases, and its community places great importance on its development. An advanced optimizer system serves as the cornerstone of DuckDB's excellent query performance. The optimizer's code structure is exceptionally clear and highly extensible, implementing a vast number of optimization rules. It holds significant learning value for database kernel developers. The optimizer is an algorithm-intensive module in a database, so understanding the underlying algorithms is more important than explaining the source code line by line. Therefore, this article will focus on explaining the purpose of all optimization rules implemented in DuckDB. We will only perform a source-code-level analysis for the EXPRESSION_REWRITER optimization rule. We hope that by reading this article, you can quickly grasp the implementation of DuckDB's optimizer and learn how to develop new rules.

DuckDB's optimizer is encapsulated within the Optimizer class. This class has very simple member variables, just four of them:

• context: A reference to the client context.

• binder: The binder is needed because the optimizer might add new operators while rewriting the logical plan.

• rewriter: The expression rewriter. DuckDB encapsulates all rules related to expression rewriting in the expression rewriter for unified management.

• plan: The optimized logical plan.

The class also has only three core member functions:

• Optimize: The entry point for the optimization process.

• OptimizerDisabled: DuckDB can disable specific optimization rules via the global variable disabled_optimizers. This function reads this variable to check if an optimization is disabled.

• RunBuiltInOptimizers: Runs DuckDB's built-in optimizers.

• RunOptimizer: Runs a specific optimization rule.

• Verify: Checks if the current logical plan is valid.

• BindScalarFunction: The optimizer might create new functions during the optimization process, which need to be bound.

class Optimizer {

public:

Optimizer(Binder &binder, ClientContext &context);

//! Optimize a plan by running specialized optimizers

// The entry point for the optimization process.

unique_ptr<LogicalOperator> Optimize(unique_ptr<LogicalOperator> plan);

//! Return a reference to the client context of this optimizer

// Gets the context of the current client thread.

ClientContext &GetContext();

//! Whether the specific optimizer is disabled

// Checks if a specific optimizer is disabled.

bool OptimizerDisabled(OptimizerType type);

static bool OptimizerDisabled(ClientContext &context, OptimizerType type);

public:

// A reference to the client context.

ClientContext &context;

// The binder is needed because the optimizer might add new operators while rewriting the logical plan.

Binder &binder;

// The expression rewriter.

ExpressionRewriter rewriter;

private:

// Run the built-in optimizers.

void RunBuiltInOptimizers();

// Run a specific optimization rule.

void RunOptimizer(OptimizerType type, const std::function<void()> &callback);

// Verify if the current logical plan is valid.

void Verify(LogicalOperator &op);

public:

// helper functions

// Helper functions. The optimizer might need to create new functions during optimization, so they need to be bound.

unique_ptr<Expression> BindScalarFunction(const string &name, unique_ptr<Expression> c1);

unique_ptr<Expression> BindScalarFunction(const string &name, unique_ptr<Expression> c1, unique_ptr<Expression> c2);

private:

// The optimized logical plan.

unique_ptr<LogicalOperator> plan;

private:

unique_ptr<Expression> BindScalarFunction(const string &name, vector<unique_ptr<Expression>> children);

};Next, let's look at the entry function for the optimization logic, Optimizer::Optimize:

unique_ptr<LogicalOperator> Optimizer::Optimize(unique_ptr<LogicalOperator> plan_p) {

// Verifies if the current plan is a valid logical plan, only active in Debug mode.

Verify(*plan_p);

this->plan = std::move(plan_p);

// Iterate over all optimizer_extensions and call the pre_optimize_function.

for (auto &pre_optimizer_extension : DBConfig::GetConfig(context).optimizer_extensions) {

RunOptimizer(OptimizerType::EXTENSION, [&]() {

OptimizerExtensionInput input {GetContext(), *this, pre_optimizer_extension.optimizer_info.get()};

if (pre_optimizer_extension.pre_optimize_function) {

pre_optimizer_extension.pre_optimize_function(input, plan);

}

});

}

// Run DuckDB's built-in optimizers.

RunBuiltInOptimizers();

// Iterate over all optimizer_extensions and call the optimize_function.

for (auto &optimizer_extension : DBConfig::GetConfig(context).optimizer_extensions) {

RunOptimizer(OptimizerType::EXTENSION, [&]() {

OptimizerExtensionInput input {GetContext(), *this, optimizer_extension.optimizer_info.get()};

if (optimizer_extension.optimize_function) {

optimizer_extension.optimize_function(input, plan);

}

});

}

// Verify that the optimized plan is a valid execution plan.

Planner::VerifyPlan(context, plan);

return std::move(plan);

}This function takes an unoptimized logical plan as input and outputs an optimized logical plan, which is represented by its top-level logical operator.

DuckDB is designed to be very friendly to plugins, allowing developers to customize DuckDB's optimization flow. Therefore, the entire optimization process is divided into three parts:

Let's briefly see how to customize an optimizer extension for DuckDB. All DuckDB optimizer plugins must inherit from the OptimizerExtension class. Its definition is quite simple, with only three member variables: the optimize_function and pre_optimize_function we mentioned earlier, and some additional information to be passed to the extension.

class OptimizerExtension {

public:

//! The optimize function of the optimizer extension.

//! Takes a logical query plan as an input, which it can modify in place

//! This runs, after the DuckDB optimizers have run

optimize_function_t optimize_function = nullptr;

//! The pre-optimize function of the optimizer extension.

//! Takes a logical query plan as an input, which it can modify in place

//! This runs, before the DuckDB optimizers have run

pre_optimize_function_t pre_optimize_function = nullptr;

//! Additional optimizer info passed to the optimize functions

shared_ptr<OptimizerExtensionInfo> optimizer_info;

};The file loadable_extension_optimizer_demo.cpp shows us how to add a custom optimization rule to DuckDB. Interested readers can explore it on their own.

DuckDB's built-in optimizer contains a total of 26 optimization rules: EXPRESSION_REWRITER, SUM_REWRITER, FILTER_PULLUP, FILTER_PUSHDOWN, CTE_FILTER_PUSHER, REGEX_RANGE, IN_CLAUSE, DELIMINATOR, EMPTY_RESULT_PULLUP, JOIN_ORDER, UNNEST_REWRITER, UNUSED_COLUMNS, DUPLICATE_GROUPS, COMMON_SUBEXPRESSIONS, COLUMN_LIFETIME, BUILD_SIDE_PROBE_SIDE, LIMIT_PUSHDOWN, SAMPLING_PUSHDOWN, TOP_N, LATE_MATERIALIZATION, STATISTICS_PROPAGATION, COMMON_AGGREGATE, REORDER_FILTER, JOIN_FILTER_PUSHDOWN, MATERIALIZED_CTE, and COMPRESSED_MATERIALIZATION. This article will briefly describe these 26 rules to give readers an idea of what optimizations they perform. Four of these, DELIMINATOR, JOIN_ORDER, UNNEST_REWRITER, and BUILD_SIDE_PROBE_SIDE, involve the Join Reorder algorithm and subquery handling, which are relatively complex and will be covered in separate future articles.

In the Optimizer::RunBuiltInOptimizers function, we can see that the optimizer sequentially calls Optimizer::RunOptimizer to optimize the logical plan with different rules:

void Optimizer::RunBuiltInOptimizers() {

switch (plan->type) {

case LogicalOperatorType::LOGICAL_TRANSACTION:

case LogicalOperatorType::LOGICAL_PRAGMA:

case LogicalOperatorType::LOGICAL_SET:

case LogicalOperatorType::LOGICAL_UPDATE_EXTENSIONS:

case LogicalOperatorType::LOGICAL_CREATE_SECRET:

case LogicalOperatorType::LOGICAL_EXTENSION_OPERATOR:

// skip optimizing simple & often-occurring plans unaffected by rewrites

if (plan->children.empty()) {

return;

}

break;

default:

break;

}

// first we perform expression rewrites using the ExpressionRewriter

// this does not change the logical plan structure, but only simplifies the expression trees

RunOptimizer(OptimizerType::EXPRESSION_REWRITER, [&]() { rewriter.VisitOperator(*plan); });

// Rewrites SUM(x + C) into SUM(x) + C * COUNT(x)

RunOptimizer(OptimizerType::SUM_REWRITER, [&]() {

SumRewriterOptimizer optimizer(*this);

optimizer.Optimize(plan);

});

// perform filter pullup

RunOptimizer(OptimizerType::FILTER_PULLUP, [&]() {

FilterPullup filter_pullup;

plan = filter_pullup.Rewrite(std::move(plan));

});

// perform filter pushdown

RunOptimizer(OptimizerType::FILTER_PUSHDOWN, [&]() {

FilterPushdown filter_pushdown(*this);

unordered_set<idx_t> top_bindings;

filter_pushdown.CheckMarkToSemi(*plan, top_bindings);

plan = filter_pushdown.Rewrite(std::move(plan));

});

...

}Let's first look at the implementation of Optimizer::RunOptimizer:

void Optimizer::RunOptimizer(OptimizerType type, const std::function<void()> &callback) {

if (OptimizerDisabled(type)) {

// optimizer is marked as disabled: skip

return;

}

auto &profiler = QueryProfiler::Get(context);

profiler.StartPhase(MetricsUtils::GetOptimizerMetricByType(type));

callback();

profiler.EndPhase();

if (plan) {

Verify(*plan);

}

}This function is very simple. The first parameter is an enum type for an optimization rule, and the second is a callback function. The function first calls Optimizer::OptimizerDisabled to check if the optimization is disabled. If so, it returns directly. If not disabled, it uses the callback function to optimize the logical plan. If the profiler is enabled, it also records the phase.

So, the real optimization work is done by the callback function passed to Optimizer::RunOptimizer. Due to space constraints, we will focus on explaining EXPRESSION_REWRITER in detail and only briefly describe the purpose of the other optimization rules.

EXPRESSION_REWRITER is the first optimization rule, implemented by calling the rewriter's VisitOperator.

// first we perform expression rewrites using the ExpressionRewriter

// this does not change the logical plan structure, but only simplifies the expression trees

RunOptimizer(OptimizerType::EXPRESSION_REWRITER, [&]() { rewriter.VisitOperator(*plan); });As we mentioned in the previous section, rewriter is a member variable of Optimizer and is an instance of the ExpressionRewriter class. The rewrite rules it applies are added in the Optimizer's constructor:

Optimizer::Optimizer(Binder &binder, ClientContext &context) : context(context), binder(binder), rewriter(context) {

rewriter.rules.push_back(make_uniq<ConstantFoldingRule>(rewriter));

rewriter.rules.push_back(make_uniq<DistributivityRule>(rewriter));

rewriter.rules.push_back(make_uniq<ArithmeticSimplificationRule>(rewriter));

rewriter.rules.push_back(make_uniq<CaseSimplificationRule>(rewriter));

rewriter.rules.push_back(make_uniq<ConjunctionSimplificationRule>(rewriter));

rewriter.rules.push_back(make_uniq<DatePartSimplificationRule>(rewriter));

rewriter.rules.push_back(make_uniq<ComparisonSimplificationRule>(rewriter));

rewriter.rules.push_back(make_uniq<InClauseSimplificationRule>(rewriter));

rewriter.rules.push_back(make_uniq<EqualOrNullSimplification>(rewriter));

rewriter.rules.push_back(make_uniq<MoveConstantsRule>(rewriter));

rewriter.rules.push_back(make_uniq<LikeOptimizationRule>(rewriter));

rewriter.rules.push_back(make_uniq<OrderedAggregateOptimizer>(rewriter));

rewriter.rules.push_back(make_uniq<DistinctAggregateOptimizer>(rewriter));

rewriter.rules.push_back(make_uniq<DistinctWindowedOptimizer>(rewriter));

rewriter.rules.push_back(make_uniq<RegexOptimizationRule>(rewriter));

rewriter.rules.push_back(make_uniq<EmptyNeedleRemovalRule>(rewriter));

rewriter.rules.push_back(make_uniq<EnumComparisonRule>(rewriter));

rewriter.rules.push_back(make_uniq<JoinDependentFilterRule>(rewriter));

rewriter.rules.push_back(make_uniq<TimeStampComparison>(context, rewriter));

#ifdef DEBUG

for (auto &rule : rewriter.rules) {

// root not defined in rule

D_ASSERT(rule->root);

}

#endif

}EXPRESSION_REWRITER has a total of 19 rules. Let's briefly describe them:

• ConstantFoldingRule: Constant folding optimization. It computes the value of constant expressions during the optimization phase and replaces the expression with the result.

• DistributivityRule: Applies the distributive law to boolean expressions, e.g., transforming (X AND B) OR (X AND C) OR (X AND D) into X AND (B OR C OR D).

• ArithmeticSimplificationRule: Simplifies arithmetic expressions with known outcomes, e.g., X * 0 is always 0, regardless of X.

• CaseSimplificationRule: Optimizes conditional expressions. If a conditional expression contains constants that can be evaluated, the result of the expression can be determined, e.g., CASE WHEN 1=1 THEN x ELSE y END is definitely x.

• ConjunctionSimplificationRule: Optimizes boolean expressions. If a boolean expression contains constants, the result can be directly computed.

• DatePartSimplificationRule: Optimizes the date_part function. In DuckDB, date_part has two input parameters: the time part to extract and the date. For example, date_part('year', col1) extracts the year from col1. When the first argument of date_part is a constant, this function is equivalent to a dedicated function like year(col1). year(col1) is faster than date_part('year', col1) because it doesn't need to parse the first argument on each evaluation.

• ComparisonSimplificationRule: Optimizes comparison expressions. An expression like X = NULL can be directly replaced with NULL. For other expressions, if the left side is a column with a type cast function and the right side is a constant, it tries to apply the cast to the constant on the right, reducing the number of cast function calls.

• InClauseSimplificationRule: Optimizes IN clauses. When the left side of an IN clause is a column with a type cast and the right side is a set of constants, it tries to apply the cast to the constants on the right to reduce cast function calls.

• EqualOrNullSimplification: Optimizes EqualOrNull expressions. An expression like A=B OR (A IS NULL AND B IS NULL) is essentially NULL-safe equal logic (like A <=> B in MySQL). It converts such expressions to A <=> B.

• MoveConstantsRule: Rearranges terms in comparison expressions, e.g., X + 1 = 100 is equivalent to X = 99.

• LikeOptimizationRule: Optimizes LIKE functions. When the pattern meets certain conditions, LIKE can be converted to prefix, suffix, or contains functions, which are more efficient.

• OrderedAggregateOptimizer: Optimizes aggregate functions with an ORDER BY clause. For an aggregate like sum(A ORDER BY B), the ORDER BY B is completely useless and can be simplified to sum(A).

• DistinctAggregateOptimizer: Optimizes aggregate functions with DISTINCT. For an aggregate like max(DISTINCT A), the DISTINCT is useless and can be simplified to max(A).

• DistinctWindowedOptimizer: Similar to DistinctAggregateOptimizer, if a window function doesn't inherently require DISTINCT, it can be simplified.

• RegexOptimizationRule: Optimizes regex functions. It checks if a regex can be simplified to a LIKE function, and further to prefix, suffix, or contains functions.

• EmptyNeedleRemovalRule: Optimizes prefix functions. When the second argument of a prefix function is an empty string, it can be converted to a constant_or_null function for better efficiency.

• EnumComparisonRule: Optimizes comparisons between ENUM types. When two enum types are compared, it determines if they can ever be equal based on their enum values. If not, it's replaced with a constant_or_null function for higher efficiency.

• JoinDependentFilterRule: Splits complex join conditions. A complex join condition might be splittable, and the resulting sub-conditions can be evaluated early on each side of the join, reducing its complexity.

• TimeStampComparison: Optimizes timestamp comparisons. When a timestamp type is compared for equality with a date type cast from a VARCHAR constant, it converts the equality check into a range comparison. For example, cast(ts as date) = cast('2020-01-01' as date) is converted to ts >= '2020-01-01 00:00:00'::TIMESTAMP AND ts < '2020-01-02 00:00:00'::TIMESTAMP.

ExpressionRewriter Code AnalysisNext, let's see how ExpressionRewriter applies these 19 rules. ExpressionRewriter inherits from the base class LogicalOperatorVisitor, which provides an excellent method for traversing logical operators and the expressions within them. Any future optimization that needs to identify and optimize a certain type of expression can inherit from LogicalOperatorVisitor.

class LogicalOperatorVisitor {

public:

virtual ~LogicalOperatorVisitor() {

}

virtual void VisitOperator(LogicalOperator &op);

virtual void VisitExpression(unique_ptr<Expression> *expression);

static void EnumerateExpressions(LogicalOperator &op,

const std::function<void(unique_ptr<Expression> *child)> &callback);

...

protected:

virtual unique_ptr<Expression> VisitReplace(BoundAggregateExpression &expr, unique_ptr<Expression> *expr_ptr);

virtual unique_ptr<Expression> VisitReplace(BoundBetweenExpression &expr, unique_ptr<Expression> *expr_ptr);

...

};Simply put, LogicalOperatorVisitor provides three virtual functions:

• VisitOperator: Visits the children of a logical operator and then the expressions within the operator itself.

• VisitExpression: Visits an expression and, based on its type, executes a VisitReplace function.

• VisitReplace: Replaces an expression of a specific type. There is an overloaded VisitReplace function for each expression type.

LogicalOperatorVisitor also provides a function VisitOperatorExpressions, which enumerates expressions based on the operator type and executes VisitExpression. This function calls EnumerateExpressions to get the expressions from the operator and then executes VisitExpression. The implementation of EnumerateExpressions is very simple: it just type-casts based on the logical operator's type to access its expression parts.

void LogicalOperatorVisitor::EnumerateExpressions(LogicalOperator &op,

const std::function<void(unique_ptr<Expression> *child)> &callback) {

switch (op.type) {

case LogicalOperatorType::LOGICAL_EXPRESSION_GET: {

auto &get = op.Cast<LogicalExpressionGet>();

for (auto &expr_list : get.expressions) {

for (auto &expr : expr_list) {

callback(&expr);

}

}

break;

}

case LogicalOperatorType::LOGICAL_ORDER_BY: {

auto &order = op.Cast<LogicalOrder>();

for (auto &node : order.orders) {

callback(&node.expression);

}

break;

}

case LogicalOperatorType::LOGICAL_TOP_N: {

auto &order = op.Cast<LogicalTopN>();

for (auto &node : order.orders) {

callback(&node.expression);

}

break;

}

....

}

}This kind of switch logic based on operator type is very common in DuckDB's optimizer code. In a sense, an optimization rule is all about checking if an operator meets certain conditions and applying the corresponding rule if it does.

ExpressionRewriter overrides VisitOperator and reuses the VisitOperatorExpressions function. Let's first look at ExpressionRewriter::VisitOperator:

void ExpressionRewriter::VisitOperator(LogicalOperator &op) {

// Rewrite in a bottom-up manner.

VisitOperatorChildren(op);

this->op = &op;

// to_apply_rules contains all the rules.

to_apply_rules.clear();

for (auto &rule : rules) {

to_apply_rules.push_back(*rule);

}

// Rewrite expressions in the current logical operator.

VisitOperatorExpressions(op);

// If it is a LogicalFilter, we split up filter conjunctions again.

// if it is a LogicalFilter, we split up filter conjunctions again

if (op.type == LogicalOperatorType::LOGICAL_FILTER) {

auto &filter = op.Cast<LogicalFilter>();

filter.SplitPredicates();

}

}The entire rewrite process is bottom-up, traversing the whole logical plan. It rewrites the child nodes first, then calls LogicalOperatorVisitor::VisitOperatorExpressions to get the expressions in the current logical operator.

After getting the expressions, it uses ExpressionRewriter::VisitExpression to apply the rules. The process of ExpressionRewriter::VisitExpression is to repeatedly call ExpressionRewriter::ApplyRules to try to apply rewrite rules until the expression no longer changes.

void ExpressionRewriter::VisitExpression(unique_ptr<Expression> *expression) {

bool changes_made;

do {

changes_made = false;

*expression = ExpressionRewriter::ApplyRules(*op, to_apply_rules, std::move(*expression), changes_made, true);

} while (changes_made);

}ExpressionRewriter::ApplyRules is a loop that traverses the 19 rules and applies them in a top-down manner:

unique_ptr<Expression> ExpressionRewriter::ApplyRules(LogicalOperator &op, const vector<reference<Rule>> &rules,

unique_ptr<Expression> expr, bool &changes_made, bool is_root) {

for (auto &rule : rules) {

vector<reference<Expression>> bindings;

// The root of each rule is an ExpressionMatcher, responsible for checking if the current expression meets the application criteria.

if (rule.get().root->Match(*expr, bindings)) {

// the rule matches! try to apply it

bool rule_made_change = false;

auto alias = expr->alias;

// Apply the rule to rewrite the expression.

auto result = rule.get().Apply(op, bindings, rule_made_change, is_root);

// If result is returned, it means the rule was applied and the expression type changed.

if (result) {

changes_made = true;

// the base node changed: the rule applied changes

// rerun on the new node

if (!alias.empty()) {

result->alias = std::move(alias);

}

// Return the modified expression. The entire expression type has changed.

// For example, if a function's arguments are all constants, applying ConstantFoldingRule would replace the FunctionExpression with a ConstantExpression.

return ExpressionRewriter::ApplyRules(op, rules, std::move(result), changes_made);

// No result returned, but rule_made_change is true, meaning the expression type didn't change, but its children might have.

// For example, `X + 1 = 100` becomes `X = 99` via MoveConstantsRule, but the expression itself is still a ComparisonExpression.

} else if (rule_made_change) {

changes_made = true;

// the base node didn't change, but changes were made, rerun

return expr;

}

// No changes were made, continue to the next rule.

// else nothing changed, continue to the next rule

continue;

}

}

// No more optimizations can be applied to this expression, so recursively process its children.

// no changes could be made to this node

// recursively run on the children of this node

ExpressionIterator::EnumerateChildren(*expr, [&](unique_ptr<Expression> &child) {

child = ExpressionRewriter::ApplyRules(op, rules, std::move(child), changes_made);

});

return expr;

}For any Rule, there are two crucial points:

All rules inherit from a base class Rule. The core part of Rule is a member variable root, which is a unique_ptr<ExpressionMatcher> responsible for matching expressions, and a pure virtual function Apply for applying the rewrite.

class Rule {

public:

explicit Rule(ExpressionRewriter &rewriter) : rewriter(rewriter) {

}

virtual ~Rule() {

}

//! The expression rewriter this rule belongs to

ExpressionRewriter &rewriter;

//! The expression matcher of the rule

unique_ptr<ExpressionMatcher> root;

ClientContext &GetContext() const;

virtual unique_ptr<Expression> Apply(LogicalOperator &op, vector<reference<Expression>> &bindings,

bool &fixed_point, bool is_root) = 0;

};MoveConstantsRule inherits from Rule. It just needs to initialize its root in its constructor and override the virtual function Apply to implement its basic functionality.

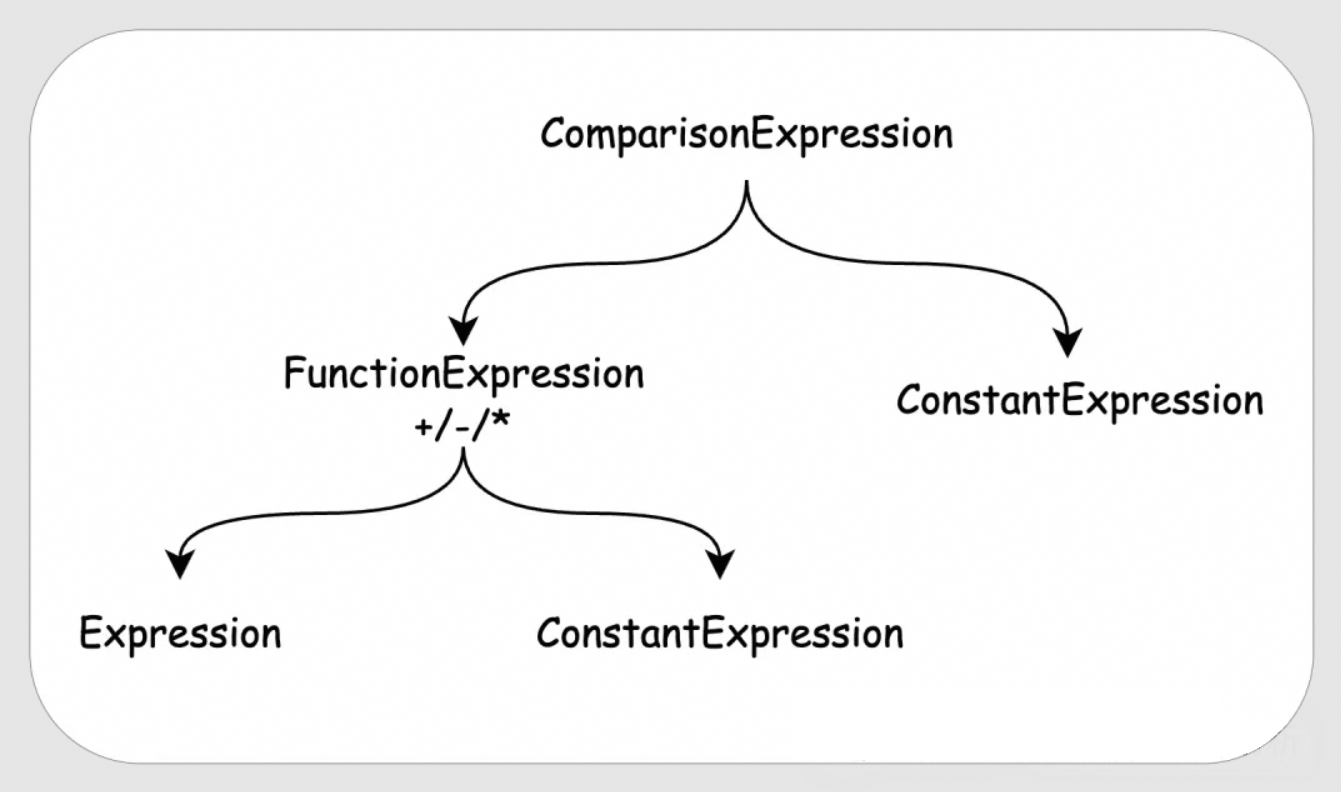

We know that MoveConstantsRule needs to match expressions of the following format:

Expression { + | - | * } ConstantExpression CompareExpression ConstantExpressionThe syntax tree for this expression looks like this:

Building the root for MoveConstantsRule is essentially representing this syntax tree again:

MoveConstantsRule::MoveConstantsRule(ExpressionRewriter &rewriter) : Rule(rewriter) {

// The top level is a ComparisonExpression, so create a ComparisonExpressionMatcher.

auto op = make_uniq<ComparisonExpressionMatcher>();

// One of the children of ComparisonExpression is a ConstantExpression.

op->matchers.push_back(make_uniq<ConstantExpressionMatcher>());

// The order of ConstantExpression and Function doesn't matter, so set the matching policy to UNORDERED.

op->policy = SetMatcher::Policy::UNORDERED;

// The other child of ComparisonExpression is a FunctionExpression.

auto arithmetic = make_uniq<FunctionExpressionMatcher>();

// we handle multiplication, addition and subtraction because those are "easy"

// integer division makes the division case difficult

// e.g. [x / 2 = 3] means [x = 6 OR x = 7] because of truncation -> no clean rewrite rules

// We only move terms for + / - / *, so arithmetic->function is a ManyFunctionMatcher, matching multiple functions.

arithmetic->function = make_uniq<ManyFunctionMatcher>(unordered_set<string> {"+", "-", "*"});

// we match only on integral numeric types

// We require the expression's return type to be integral, as moving terms for floating-point numbers can change the result.

arithmetic->type = make_uniq<IntegerTypeMatcher>();

// The two children of FunctionExpression are an Expression and a ConstantExpression.

auto child_constant_matcher = make_uniq<ConstantExpressionMatcher>();

auto child_expression_matcher = make_uniq<ExpressionMatcher>();

child_constant_matcher->type = make_uniq<IntegerTypeMatcher>();

child_expression_matcher->type = make_uniq<IntegerTypeMatcher>();

arithmetic->matchers.push_back(std::move(child_constant_matcher));

arithmetic->matchers.push_back(std::move(child_expression_matcher));

arithmetic->policy = SetMatcher::Policy::SOME;

op->matchers.push_back(std::move(arithmetic));

root = std::move(op);

}ComparisonExpressionMatcher is responsible for matching a ComparisonExpression and then uses its matchers to match its children. The entire matching process is top-down, and it adds the matched Expressions to the bindings vector along the way.

bool ComparisonExpressionMatcher::Match(Expression &expr_p, vector<reference<Expression>> &bindings) {

if (!ExpressionMatcher::Match(expr_p, bindings)) {

return false;

}

auto &expr = expr_p.Cast<BoundComparisonExpression>();

vector<reference<Expression>> expressions;

expressions.push_back(*expr.left);

expressions.push_back(*expr.right);

return SetMatcher::Match(matchers, expressions, bindings, policy);

}So, after a successful match, bindings[0] will be a ComparisonExpression, bindings[1] a ConstantExpression, bindings[2] a FunctionExpression, bindings[3] another ConstantExpression, and bindings[4] an Expression.

Next is writing the MoveConstantsRule::Apply function. As you can see, it indeed retrieves all expressions from bindings as we described, and then it manipulates the expression. You can follow the code comments to understand the whole process.

unique_ptr<Expression> MoveConstantsRule::Apply(LogicalOperator &op, vector<reference<Expression>> &bindings,

bool &changes_made, bool is_root) {

auto &comparison = bindings[0].get().Cast<BoundComparisonExpression>();

auto &outer_constant = bindings[1].get().Cast<BoundConstantExpression>();

auto &arithmetic = bindings[2].get().Cast<BoundFunctionExpression>();

auto &inner_constant = bindings[3].get().Cast<BoundConstantExpression>();

D_ASSERT(arithmetic.return_type.IsIntegral());

D_ASSERT(arithmetic.children[0]->return_type.IsIntegral());

// inner_constant is the constant to be moved.

// outer_constant is the constant on the other side of the comparison.

// If inner_constant or outer_constant is NULL.

if (inner_constant.value.IsNull() || outer_constant.value.IsNull()) {

// Cannot optimize DISTINCT_FROM or NOT_DISTINCT_FROM.

if (comparison.GetExpressionType() == ExpressionType::COMPARE_DISTINCT_FROM ||

comparison.GetExpressionType() == ExpressionType::COMPARE_NOT_DISTINCT_FROM) {

return nullptr;

}

// Arithmetic with NULL results in NULL.

return make_uniq<BoundConstantExpression>(Value(comparison.return_type));

}

// Get the values of outer_constant and inner_constant.

auto &constant_type = outer_constant.return_type;

hugeint_t outer_value = IntegralValue::Get(outer_constant.value);

hugeint_t inner_value = IntegralValue::Get(inner_constant.value);

// Get the index of the Expression in arithmetic.children.

idx_t arithmetic_child_index = arithmetic.children[0].get() == &inner_constant ? 1 : 0;

auto &op_type = arithmetic.function.name;

// Addition.

if (op_type == "+") {

// [x + 1 COMP 10] OR [1 + x COMP 10]

// order does not matter in addition:

// simply change right side to 10-1 (outer_constant - inner_constant)

// Try to subtract, if it fails, return nullptr, indicating optimization failed.

if (!Hugeint::TrySubtractInPlace(outer_value, inner_value)) {

return nullptr;

}

auto result_value = Value::HUGEINT(outer_value);

// If the calculated result after moving the term cannot be cast to constant_type, special handling is needed.

if (!result_value.DefaultTryCastAs(constant_type)) {

if (comparison.GetExpressionType() != ExpressionType::COMPARE_EQUAL) {

return nullptr;

}

// if the cast is not possible then the comparison is not possible

// for example, if we have x + 5 = 3, where x is an unsigned number, we will get x = -2

// since this is not possible we can remove the entire branch here

return ExpressionRewriter::ConstantOrNull(std::move(arithmetic.children[arithmetic_child_index]),

Value::BOOLEAN(false));

}

// Set the new value for outer_constant

outer_constant.value = std::move(result_value);

} else if (op_type == "-") {

....

} else {

....

}

// replace left side with x

// first extract x from the arithmetic expression

auto arithmetic_child = std::move(arithmetic.children[arithmetic_child_index]);

// then place in the comparison

// Directly replace one side of the ComparisonExpression's children with the Expression.

if (comparison.left.get() == &outer_constant) {

comparison.right = std::move(arithmetic_child);

} else {

comparison.left = std::move(arithmetic_child);

}

changes_made = true;

return nullptr;

}Now we have a good understanding of all the rewrite rules applied in the EXPRESSION_REWRITER optimization, as well as how to add a new one. This concludes our discussion of EXPRESSION_REWRITER. Let's now look at the other optimizations.

The SUM_REWRITER optimization is very simple. For an aggregate function like SUM(col1 + 5), it can be rewritten as SUM(col1) + 5 * COUNT(col1). This optimization is more like an expression rewrite, so we won't go into detail here.

The FILTER_PULLUP and FILTER_PUSHDOWN optimizations often work together. The FILTER_PULLUP optimization pulls up filters in the logical plan. We know it's almost always better to apply filters as early as possible, as they reduce the amount of data for subsequent operators to process. So why would we want to pull them up?

The purpose of FILTER_PULLUP is to lift filter conditions from both sides of JOIN, EXCEPT, and INTERSECT operators. After being pulled up, these conditions can often be combined and optimized based on the operator type to derive stronger filter conditions. Then, FILTER_PUSHDOWN pushes these filters as far down the plan as possible to complete the optimization.

Consider this case:

CREATE TABLE t1 (

id INT,

col1 INT

);

INSERT INTO t1 VALUES (1, 1), (2, 2);

SELECT *

FROM (

SELECT *

FROM t1

WHERE id = 1

) d1, (

SELECT *

FROM t1

) d2

WHERE d1.id = d2.col1;The FILTER_PULLUP operation will integrate d1.id = 1 and d1.id = d2.col1, deriving the combined filter condition d1.id = 1 AND d1.id = d2.col1.

First, let's introduce two useful parameters: explain_output and disabled_optimizers. By default, DuckDB's EXPLAIN statement only shows the physical plan. However, by setting SET explain_output = 'all', you can make DuckDB display the unoptimized logical plan, the optimized logical plan, and the physical plan. We will use EXPLAIN to observe the impact of optimizations on the operators. By default, all 26 of DuckDB's built-in optimizations are enabled. We can use the disabled_optimizers parameter to disable some of them.

For example, to observe the result of FILTER_PULLUP by disabling all other optimizations, we can configure:

SET explain_output = 'all';

SET disabled_optimziers = 'EXPRESSION_REWRITER,SUM_REWRITER,FILTER_PUSHDOWN,CTE_FILTER_PUSHER,REGEX_RANGE,IN_CLAUSE,DELIMINATOR,EMPTY_RESULT_PULLUP,JOIN_ORDER,UNNEST_REWRITER,UNUSED_COLUMNS,DUPLICATE_GROUPS,COMMON_SUBEXPRESSIONS,COLUMN_LIFETIME,BUILD_SIDE_PROBE_SIDE,LIMIT_PUSHDOWN,SAMPLING_PUSHDOWN,TOP_N,LATE_MATERIALIZATION,STATISTICS_PROPAGATION,COMMON_AGGREGATE,COLUMN_LIFETIME,REORDER_FILTER,JOIN_FILTER_PUSHDOWN,MATERIALIZED_CTE,COMPRESSED_MATERIALIZATION';Then execute EXPLAIN to observe the plan:

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Unoptimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ id │

│ col1 │

│ id │

│ col1 │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ FILTER │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ (id = col1) │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ CROSS_PRODUCT │

│ ──────────────────── ├──────────────┐

└─────────────┬─────────────┘ │

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ PROJECTION ││ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: ││ Expressions: │

│ id ││ id │

│ col1 ││ col1 │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ FILTER ││ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: ││ Table: t1 │

│ (id = CAST(1 AS INTEGER)) ││ Type: Sequential Scan │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘└───────────────────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan │

└───────────────────────────┘

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ id │

│ col1 │

│ id │

│ col1 │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ FILTER │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ (id = col1) │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ FILTER │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: (id = 1) │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ CROSS_PRODUCT │

│ ──────────────────── ├──────────────┐

└─────────────┬─────────────┘ │

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ PROJECTION ││ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: ││ Expressions: │

│ id ││ id │

│ col1 ││ col1 │

│ ││ │

│ ~2 Rows ││ ~2 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN ││ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 ││ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan ││ Type: Sequential Scan │

└───────────────────────────┘└───────────────────────────┘You can see that before optimization, the FILTER for id = 1 was above the SEQ_SCAN of the t1 table. After optimization, this filter condition has been pulled up above the CROSS_PRODUCT.

FILTER_PULLUP alone is not beneficial; in fact, it can worsen the plan by delaying the filter. It needs to be combined with FILTER_PUSHDOWN. Let's enable FILTER_PUSHDOWN and look at the plan:

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ id │

│ col1 │

│ col2 │

│ id │

│ col1 │

│ col2 │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ COMPARISON_JOIN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Join Type: INNER │

│ ├──────────────┐

│ Conditions: │ │

│ (id = col1) │ │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘ │

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ PROJECTION ││ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: ││ Expressions: │

│ id ││ id │

│ col1 ││ col1 │

│ col2 ││ col2 │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN ││ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── │

│ Filters: id=1 ││ Filters: col1=1 │

│ Table: t1 ││ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan ││ Type: Sequential Scan │

└───────────────────────────┘└───────────────────────────┘As you can see, id = 1 is now pushed down as far as possible to the SEQ_SCAN, meaning the data is filtered as it's being scanned. Furthermore, d1.id = 1 AND d1.id = d2.col1 allows the optimizer to infer the filter condition d2.col1=1, which is also pushed down into the other SEQ_SCAN.

The CTE_FILTER_PUSHER optimization also pushes down filters, but specifically into Common Table Expressions (CTEs). We know that a CTE differs from a regular derived table in that it can be referenced multiple times within a query, much like creating a temporary table. Therefore, its filter pushdown requires special handling.

For example, consider the following SQL:

WITH tt AS (

SELECT max(id), col1

FROM t1

GROUP BY col1

)

SELECT *

FROM tt d1, tt d2

WHERE d1.col1 = 1 AND d2.col1 = 2;The conditions d1.col1 = 1 AND d2.col1 = 2 can be pushed down into the CTE expression. Without this pushdown (by disabling the CTE_FILTER_PUSHER optimization), the execution plan would look as follows:

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ max(id) │

│ col1 │

│ max(id) │

│ col1 │

│ │

│ ~1 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ CTE │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Table Index: 0 ├──────────────┐

│ │ │

│ ~1 Rows │ │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘ │

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ PROJECTION ││ CROSS_PRODUCT │

│ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: ││ │

│ max(id) ││ ├──────────────┐

│ col1 ││ │ │

│ ││ │ │

│ ~1 Rows ││ ~1 Rows │ │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘└─────────────┬─────────────┘ │

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ AGGREGATE ││ FILTER ││ FILTER │

│ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── │

│ Groups: col1 ││ Expressions: ││ Expressions: │

│ Expressions: max(id) ││ (col1 = 1) ││ (col1 = 2) │

│ ││ ││ │

│ ~1 Rows ││ ~1 Rows ││ ~1 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘└─────────────┬─────────────┘└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN ││ CTE_SCAN ││ CTE_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 ││ CTE Index: 0 ││ CTE Index: 0 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan ││ ││ │

│ ││ ││ │

│ ~3 Rows ││ ~1 Rows ││ ~1 Rows │

└───────────────────────────┘└───────────────────────────┘└───────────────────────────┘As you can see, when generating the tt table, there are no filter conditions. This means that even though we ultimately only need data from tt where col1 = 1 and col1 = 2, we still need to perform a full table scan on t1 to generate tt.

If we push down the filters, we get this plan:

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ max(id) │

│ col1 │

│ max(id) │

│ col1 │

│ │

│ ~1 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ CTE │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Table Index: 0 ├──────────────┐

│ │ │

│ ~1 Rows │ │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘ │

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ PROJECTION ││ CROSS_PRODUCT │

│ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: ││ │

│ max(id) ││ ├──────────────┐

│ col1 ││ │ │

│ ││ │ │

│ ~0 Rows ││ ~1 Rows │ │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘└─────────────┬─────────────┘ │

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ AGGREGATE ││ FILTER ││ FILTER │

│ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── │

│ Groups: col1 ││ Expressions: ││ Expressions: │

│ Expressions: max(id) ││ (col1 = 1) ││ (col1 = 2) │

│ ││ ││ │

│ ~0 Rows ││ ~0 Rows ││ ~0 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘└─────────────┬─────────────┘└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ FILTER ││ CTE_SCAN ││ CTE_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: ││ CTE Index: 0 ││ CTE Index: 0 │

│ ((col1 = 1) OR (col1 = 2))││ ││ │

│ ││ ││ │

│ ~1 Rows ││ ~0 Rows ││ ~0 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘└───────────────────────────┘└───────────────────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Filters: │

│ optional: col1=1 OR col1=2│

│ │

│ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan │

│ │

│ ~3 Rows │

└───────────────────────────┘The filter condition col1=1 OR col1=2 is indeed pushed down to the t1 table. Now, we only need to scan the data in t1 where col1=1 OR col1=2 to generate the tt table.

This rule rewrites the regexp_full_match function. For certain regular expression patterns with a prefix, like a[1-9], we can infer that any matching string must be greater than or equal to a1 and less than or equal to a9. Since evaluating regular expressions is generally expensive, we can add a cheaper filter before the regex filter to prune data early. Here's a case to illustrate this optimization, which you can examine on your own:

CREATE TABLE t1 (

id varchar,

col1 int

);

SELECT max(id) AS max_id

FROM t1

GROUP BY col1

HAVING regexp_full_match(max_id, 'a[1-9]');Without REGEX_RANGE enabled:

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: max_id │

│ │

│ ~0 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ FILTER │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ regexp_full_match(max_id, │

│ 'a[1-9]') │

│ │

│ ~0 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ AGGREGATE │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Groups: col1 │

│ Expressions: max(id) │

│ │

│ ~0 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan │

│ │

│ ~0 Rows │

└───────────────────────────┘With REGEX_RANGE:

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: max_id │

│ │

│ ~0 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ FILTER │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ regexp_full_match(max_id, │

│ 'a[1-9]') │

│ │

│ ~0 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ FILTER │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ ((max_id >= 'a1'::BLOB) │

│ AND (max_id <= 'a9'::BLOB│

│ )) │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ AGGREGATE │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Groups: col1 │

│ Expressions: max(id) │

│ │

│ ~0 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan │

│ │

│ ~0 Rows │

└───────────────────────────┘The IN_CLAUSE optimization converts IN clauses based on the number of elements.

If there is only one element in the IN list, it's converted to an equality comparison. For example, col1 IN (1) becomes col1 = 1.

If there are more than one but fewer than four elements, it's converted to a series of equality comparisons connected by OR. For example, col1 IN (1,2,3,4) becomes col1 = 1 OR col1 = 2 OR col1 = 3 OR col1 = 4.

If there are more elements, it will be executed using a MARK JOIN.

The DELIMINATOR optimization is related to subquery handling. This optimization is quite complex and will not be covered in detail here. A future article will be dedicated to it.

After FILTER_PULLUP and FILTER_PUSHDOWN, it's possible to have an EMPTY_RESULT if a filter is always false. When a table is joined with an EMPTY_RESULT, the result is also guaranteed to be an EMPTY_RESULT. In such cases, there is no need to read the other table. The EMPTY_RESULT_PULLUP optimization pulls up EMPTY_RESULT nodes in the logical plan to reduce the work of subsequent operators.

Here is a case:

CREATE TABLE t1 (

id int,

col1 int

);

INSERT INTO t1 VALUES (1, 1), (2, 2);

SELECT *

FROM (

SELECT *

FROM t1

WHERE id = 1

) d1, (

SELECT *

FROM t1

WHERE id = 2

) d2, (

SELECT *

FROM t1

) d3

WHERE d1.id = d2.id

AND d1.id = d3.id;Without EMPTY_RESULT_PULLUP enabled:

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ id │

│ col1 │

│ col2 │

│ id │

│ col1 │

│ col2 │

│ id │

│ col1 │

│ col2 │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ COMPARISON_JOIN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Join Type: INNER │

│ ├──────────────┐

│ Conditions: │ │

│ (id = id) │ │

│ (id = id) │ │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘ │

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ EMPTY_RESULT ││ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── │

│ ││ Expressions: │

│ ││ id │

│ ││ col1 │

│ ││ col2 │

└───────────────────────────┘└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan │

└───────────────────────────┘With EMPTY_RESULT_PULLUP enabled:

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ EMPTY_RESULT │

│ ──────────────────── │

└───────────────────────────┘The JOIN_ORDER optimization reorders the tables involved in a join. This is a complex optimization and will be covered in a dedicated article later.

UNNEST_REWRITER is responsible for rewriting the UNNEST operation within a DELIM_JOIN. This rewrite process involves DELIM_JOIN, a special type of join common in subquery processing. Therefore, we will leave this discussion for the subquery article.

DuckDB's executor and underlying storage are both columnar. Data for the same column forms a Vector, and multiple columns form a Chunk. Data is passed between operators in Chunks. Because DuckDB's storage is columnar, when reading data from a table, it's possible to read only the required columns and skip the unnecessary ones. Example:

SELECT id FROM t1;This SQL will only read the id column from table t1. With UNUSED_COLUMNS disabled:

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Physical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan │

│ │

│ ~3 Rows │

└───────────────────────────┘With UNUSED_COLUMNS enabled:

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Physical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan │

│ Projections: id │

│ │

│ ~3 Rows │

└───────────────────────────┘When UNUSED_COLUMNS is enabled, a Projections: id operation will be pushed down to the SEQ_SCAN operator, indicating that the operator should only read specific columns from the table.

Besides reading data, the UNUSED_COLUMNS optimization also applies to data passed between operators. Consider this simple SQL:

SELECT d1.id, d2.id

FROM t1 d1, t1 d2

WHERE d1.id = d2.id;After the join, we know that d1.id and d2.id are always equal. Therefore, although the Chunk provided to the next operator contains two Vectors, the second Vector is actually just a reference to the first one.

DUPLICATE_GROUPS eliminates duplicate grouping keys that may arise from optimizations like DELIMINATOR or UNUSED_COLUMNS. The effect of UNUSED_COLUMNS can be better observed with DUPLICATE_GROUPS. For the following SQL:

SELECT d1.id, d2.id

FROM t1 d1, t1 d2

WHERE d1.id = d2.id

GROUP BY d1.id, d2.id;We are performing an aggregation on the result of a join. But we know d1.id and d2.id are always the same, so GROUP BY d1.id, d2.id is equivalent to GROUP BY d1.id.

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ max(col1) │

│ │

│ ~2 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ AGGREGATE │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Groups: id │

│ │

│ Expressions: │

│ max(col1) │

│ │

│ ~2 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ COMPARISON_JOIN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Join Type: INNER │

│ Conditions: (id = id) ├──────────────┐

│ │ │

│ ~3 Rows │ │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘ │

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN ││ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 ││ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan ││ Type: Sequential Scan │

│ ││ │

│ ~3 Rows ││ ~3 Rows │

└───────────────────────────┘└───────────────────────────┘If we enable both UNUSED_COLUMNS and DUPLICATE_GROUPS, the AGGREGATE operator will only group by a single id column. If we disable either of these optimizations, the AGGREGATE operator will still group on two id columns. This is because without UNUSED_COLUMNS, d1.id and d2.id are distinct vectors. And with UNUSED_COLUMNS but without DUPLICATE_GROUPS, even though the second vector is a reference, the AGGREGATE operator won't handle this and will still group on both.

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ max(col1) │

│ │

│ ~2 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ AGGREGATE │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Groups: │

│ id │

│ id │

│ │

│ Expressions: │

│ max(col1) │

│ │

│ ~2 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ COMPARISON_JOIN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Join Type: INNER │

│ Conditions: (id = id) ├──────────────┐

│ │ │

│ ~3 Rows │ │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘ │

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN ││ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 ││ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan ││ Type: Sequential Scan │

│ ││ │

│ ~3 Rows ││ ~3 Rows │

└───────────────────────────┘└───────────────────────────┘The COMMON_SUBEXPRESSIONS optimization eliminates common subexpressions that appear in expressions. Consider the following SQL:

SELECT (id + 1) * (id + 1) FROM t1;Without optimization, the subexpression id + 1 would be calculated twice, as shown by the following execution plan:

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ ((id + 1) * (id + 1)) │

│ │

│ ~3 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan │

│ │

│ ~3 Rows │

└───────────────────────────┘However, we can first compute the value of id + 1, and then square that result.

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ (#0 * #0) │

│ │

│ ~3 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: (id + 1) │

│ │

│ ~3 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan │

│ │

│ ~3 Rows │

└───────────────────────────┘With COMMON_SUBEXPRESSIONS enabled, the plan shows an additional PROJECTION operator to pre-calculate (id + 1), reducing the total amount of computation.

The COLUMN_LIFETIME optimization is similar to UNUSED_COLUMNS. It analyzes the logical plan and removes columns that are no longer used from the plan. We will not elaborate on it here.

In the JOIN_ORDER optimization, A JOIN B is considered equivalent to B JOIN A in terms of efficiency. However, in a HASH JOIN, a smaller hash table is more CPU-cache-friendly and thus more efficient. This optimization decides which table to build the hash table on based on the estimated size of the hash table. This will be introduced together with the JOIN_ORDER optimization in a future article.

LIMIT_PUSHDOWN pushes down the LIMIT operator. Because DuckDB's executor is push-based, this pushdown can only happen when the child of the LIMIT operator is a PROJECTION operator. Furthermore, since the LIMIT operator is a pipeline breaker, the pushdown only occurs if the limit value is less than 8192. The reasons why the LIMIT operator cannot always be pushed down will be analyzed when we discuss DuckDB's executor. The limit pushdown is straightforward, as illustrated by this simple SQL:

SELECT * FROM t1 LIMIT 2;Without LIMIT_PUSHDOWN enabled:

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ LIMIT │

│ ──────────────────── │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ id │

│ col1 │

│ col2 │

│ │

│ ~3 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan │

│ │

│ ~3 Rows │

└───────────────────────────┘With LIMIT_PUSHDOWN enabled:

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ id │

│ col1 │

│ col2 │

│ │

│ ~0 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ LIMIT │

│ ──────────────────── │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan │

│ │

│ ~3 Rows │

└───────────────────────────┘SAMPLING_PUSHDOWN is an optimization that requires the TableFunction to implement a sampling_pushdown method. Let's look directly at an SQL statement:

SELECT * FROM t1 USING SAMPLE 1%;When SAMPLING_PUSHDOWN is disabled, the plan involves a full SEQ_SCAN followed by a SAMPLE operator:

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ id │

│ col1 │

│ col2 │

│ │

│ ~0 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SAMPLE │

│ ──────────────────── │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan │

└───────────────────────────┘When it's enabled, the SAMPLE operator is pushed down into the SEQ_SCAN operator:

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ id │

│ col1 │

│ col2 │

│ │

│ ~0 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Sample Method: │

│ System: 1% │

│ │

│ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan │

└───────────────────────────┘This is a simple optimization: instead of scanning the entire table and then sampling, the pushdown allows the TableFunction to only scan the required number of rows, as it supports the sampling_pushdown method.

The TOP_N optimization converts ORDER BY ... LIMIT ... into a TOP_N operator. An ORDER BY ... LIMIT ... would require sorting all the data in the table, whereas a TOP_N operator uses a heap to keep track of only the top LIMIT rows. Obviously, this optimization depends on the value of LIMIT. If the limit value is very large, a full sort might be faster. Therefore, in DuckDB, this optimization is not applied if the limit value is greater than 5000 and also greater than 0.007 of the child operator's estimated cardinality. This optimization is also quite simple, as shown by this SQL:

SELECT * FROM t1 ORDER BY col1 LIMIT 2;Without TOP_N enabled:

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ LIMIT │

│ ──────────────────── │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ ORDER_BY │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ memory.main.t1.col1 │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ id │

│ col1 │

│ col2 │

│ │

│ ~3 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan │

│ │

│ ~3 Rows │

└───────────────────────────┘With TOP_N optimization enabled and LATE_MATERIALZATION disabled: (LATE_MATERIALZATION further optimizes the logical execution plan. To observe only the impact of TOP_N, we disable LATE_MATERIALZATION.)

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ TOP_N │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ ~2 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ id │

│ col1 │

│ col2 │

│ │

│ ~3 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan │

│ │

│ ~3 Rows │

└───────────────────────────┘When observing the TOP_N optimization, we disabled LATE_MATERIALIZATION. Now let's enable LATE_MATERIALIZATION and re-examine the optimized logical plan for SELECT * FROM t1 ORDER BY col1 LIMIT 2;.

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ ORDER_BY │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ memory.main.t1.col1 │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ id │

│ col1 │

│ col2 │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ COMPARISON_JOIN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Join Type: SEMI │

│ ├──────────────┐

│ Conditions: │ │

│ (rowid = rowid) │ │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘ │

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN ││ TOP_N │

│ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 ││ │

│ Type: Sequential Scan ││ ~2 Rows │

└───────────────────────────┘└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ col1 │

│ rowid │

│ │

│ ~3 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan │

│ │

│ ~3 Rows │

└───────────────────────────┘As you can see, the SQL is now executed as a join. The execution flow is as follows:

• Read the col1 column and the corresponding rowid from table t1.

• Perform a TOP_N sort on col1 to get the rowids for the LIMIT rows.

• Use the rowids from step 2 to fetch all columns for the corresponding rows from the table.

With LATE_MATERIALIZATION enabled, the operation of materializing the full row is postponed as much as possible. Before this optimization, we had to read all columns of all rows. After, we only need to read the sorting column for all rows, and all columns for just the LIMIT rows we need. If a table has many rows, this optimization can have a huge impact.

In addition to the TOP_N operator, LATE_MATERIALIZATION provides similar optimizations for LIMIT and SAMPLE operators.

The STATISTICS_PROPAGATION optimization propagates statistical information between operators. It relies on the storage layer providing accurate min/max statistics and aims to derive min/max statistics for the intermediate results of each operator. With this information, some very effective optimizations can be achieved.

For example, with the following SQL:

CREATE TABLE t1 (id INT, col1 INT);

INSERT INTO t1 VALUES (1, 1),(5, 5);

SELECT * FROM t1 WHERE col1 > 10;Since the maximum value of col1 in table t1 is 5, we can know that the result of SELECT * FROM t1 WHERE col1 > 10; will definitely be an EMPTY_RESULT.

Another example:

SELECT min(id) FROM t1 GROUP BY col1;Since we know the minimum value of col1 in table t1 is 1 and the maximum is 5, col1 can be compressed to be represented by a tinyint. The execution plan will show internal compression and decompression functions being used.

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: min(id) │

│ │

│ ~3 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│__internal_decompress_integ│

│ ral_integer(#0, 1) │

│ #1 │

│ │

│ ~3 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ AGGREGATE │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Groups: col1 │

│ Expressions: min(id) │

│ │

│ ~3 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│__internal_compress_integra│

│ l_utinyint(#0, 1) │

│ #1 │

│ │

│ ~6 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan │

│ │

│ ~6 Rows │

└───────────────────────────┘The COMMON_AGGREGATE optimization is similar to DUPLICATE_GROUPS and eliminates duplicate aggregate functions. Let's use the following SQL to illustrate:

SELECT min(d1.id), min(d2.id)

FROM t1 d1, t1 d2

WHERE d1.id = d2.id

GROUP BY d1.col1;After the join, min(d1.id) and min(d2.id) are actually aggregating on the same column. When COMMON_AGGREGATE is disabled, the AGGREGATE operator will compute two aggregate functions. When it is enabled, it will only compute one.

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ min(id) │

│ min(id) │

│ │

│ ~1 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ AGGREGATE │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Groups: col1 │

│ │

│ Expressions: │

│ min(id) │

│ min(id) │

│ │

│ ~1 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ COMPARISON_JOIN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Join Type: INNER │

│ Conditions: (id = id) ├──────────────┐

│ │ │

│ ~3 Rows │ │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘ │

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN ││ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 ││ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan ││ Type: Sequential Scan │

│ ││ │

│ ~3 Rows ││ ~3 Rows │

└───────────────────────────┘└───────────────────────────┘When COMMON_AGGREGATE is enabled, the AGGREGATE operator will compute only one aggregate function.

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ min(id) │

│ min(id) │

│ │

│ ~1 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ AGGREGATE │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Groups: col1 │

│ Expressions: min(id) │

│ │

│ ~1 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ COMPARISON_JOIN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Join Type: INNER │

│ Conditions: (id = id) ├──────────────┐

│ │ │

│ ~3 Rows │ │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘ │

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN ││ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 ││ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan ││ Type: Sequential Scan │

│ ││ │

│ ~3 Rows ││ ~3 Rows │

└───────────────────────────┘└───────────────────────────┘The REORDER_FILTER optimization reorders multiple filter expressions within a FILTER operator. Since filter expressions are connected by AND, as soon as one expression evaluates to false, the subsequent expressions don't need to be evaluated. Therefore, DuckDB prefers to place computationally cheaper filter expressions first.

Let's use the following example to illustrate:

CREATE TABLE t1 (

id INT,

col1 INT,

col2 VARCHAR

);

EXPLAIN SELECT max(col1) AS max_col1, max(col2) AS max_col2

FROM t2

GROUP BY id

HAVING max_col2 > 'a'

AND max_col1 > 1;With REORDER_FILTER disabled:

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ max_col1 │

│ max_col2 │

│ │

│ ~0 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ FILTER │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ (max_col2 > 'a') │

│ (max_col1 > 1) │

│ │

│ ~0 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ AGGREGATE │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Groups: id │

│ │

│ Expressions: │

│ max(col2) │

│ max(col1) │

│ │

│ ~0 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan │

│ │

│ ~0 Rows │

└───────────────────────────┘With REORDER_FILTER enabled:

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ max_col1 │

│ max_col2 │

│ │

│ ~0 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ FILTER │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ (max_col1 > 1) │

│ (max_col2 > 'a') │

│ │

│ ~0 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ AGGREGATE │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Groups: id │

│ │

│ Expressions: │

│ max(col2) │

│ max(col1) │

│ │

│ ~0 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan │

│ │

│ ~0 Rows │

└───────────────────────────┘Enabling REORDER_FILTER changes the order of max_col1 > 1 and max_col2 > 'a' in the FILTER operator. DuckDB considers string comparison to be more computationally expensive, so with REORDER_FILTER enabled, max_col2 > 'a' is moved to be evaluated after max_col1 > 1.

JOIN_FILTER_PUSHDOWN is a special optimization whose changes are not reflected in the logical plan. Consider a simple SQL:

CREATE TABLE t1 (id INT, col1 INT);

CREATE TABLE t2 (id INT, col1 INT);

SELECT * FROM t1, t2 WHERE t1.col1 = t2.col1;This SQL has no filters on the tables, so it seems it can only be a simple hash join. However, after building the hash table on t2, we actually derive a new filter for table t1: t1.col1 <= max(t2.col1) AND t1.col1 >= min(t2.col1). This means we can aggregate t2.col1 to find its min and max values while building the hash table for t2. When we then read the left table (t1), this condition can be pushed down to its SEQ_SCAN operator. How this optimization is implemented will be detailed in the future article on Hash Join.

The MATERIALIZED_CTE optimization is quite simple. Only when this optimization is enabled will a CTE truly be materialized. Otherwise, every time the CTE is referenced, its expression will be re-evaluated.

Let's use the following SQL to illustrate:

EXPLAIN WITH tt AS (

SELECT max(id)

FROM t1

)

SELECT *

FROM tt d1, tt d2;Without MATERIALIZED_CTE enabled:

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│┌───────────────────────────┐│

││ Optimized Logical Plan ││

│└───────────────────────────┘│

└─────────────────────────────┘

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: │

│ max(id) │

│ max(id) │

│ │

│ ~1 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ CROSS_PRODUCT │

│ ──────────────────── ├──────────────┐

│ ~1 Rows │ │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘ │

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ PROJECTION ││ PROJECTION │

│ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: max(id) ││ Expressions: max(id) │

│ ││ │

│ ~1 Rows ││ ~1 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ AGGREGATE ││ AGGREGATE │

│ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── │

│ Expressions: max(id) ││ Expressions: max(id) │

│ ││ │

│ ~1 Rows ││ ~1 Rows │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘└─────────────┬─────────────┘

┌─────────────┴─────────────┐┌─────────────┴─────────────┐

│ SEQ_SCAN ││ SEQ_SCAN │

│ ──────────────────── ││ ──────────────────── │

│ Table: t1 ││ Table: t1 │

│ Type: Sequential Scan ││ Type: Sequential Scan │

│ ││ │