By Yi Zhan

Werewolf is a classic social deduction game. When I had just graduated, playing Werewolf was a staple during gatherings and left many interesting memories: for example, some masters, if they were not “killed” by the werewolves on the first night, everyone would think they must be a werewolf and they would have to prove their innocence during the day.

But as time passed, gathering a group of people to play Werewolf became a luxury. So, I created this AI Werewolf game using AgentScope that can start anytime. Agents can discuss, reason, and vote like real people, even learn to “lie.” Now you don’t have to wait for others; you can play a game with AI anytime, and you might not necessarily win against it.

System Requirements: Java 17+, Maven 3.6+, Bai Lian API Key (log in https://modelstudio.console.aliyun.com/us-east-1 to get it)

# Pull project source code

git clone https://github.com/agentscope-ai/agentscope-java

# Set model studio API Key (DASHSCOPE_API_KEY)

export DASHSCOPE_API_KEY=your_api_key

# Navigate to the game directory and start

cd agentscope-java/agentscope-examples/werewolf-hitl

git checkout release/1.0.5

mvn spring-boot:runOpen your browser to access http://localhost:8080, select the role you want to play, and click start the game!

When I actually started developing AI Werewolf, I found that it was far from as simple as “writing a few prompts.”

Firstly, multiple AI agents need to think continuously. They must analyze each player’s speech and behavior in every round to determine their true identity. Additionally, roles like werewolves, witches, prophets, and hunters need to decide whether to use their skills based on the actual situation during the game—none of this can be achieved with just a simple prompt.

Secondly, information must be isolated. The core enjoyment of Werewolf lies in the “information gap”: werewolves know who their teammates are, but good players do not; the results of the prophet's verification are only clear to themselves. If all agents share the same memory, the game cannot be played.

Then, a group of players takes turns speaking; can agents remember who said what? The large model API only has system/user/assistant roles and lacks the concept of “Player 5 said”. If we just dump the dialogue history onto the model, it won’t have a clue as to who said what.

Moreover, the decision-making of agents must be clear. During the voting phase, we need clear answers like “vote for Player 3” rather than vague expressions like “I think Player 3 is a bit suspicious, maybe a werewolf.” The program must be able to reliably parse the agent’s decisions; it cannot rely solely on regular expressions.

Finally, support for human players is also needed. While pure AI agent battles are interesting, it's the involvement of human players that makes a proper game.

To address these issues, we individually resolved them using AgentScope’s seven core capabilities: ReActAgent enables each agent to have the ability to think continuously; MsgHub implements automatic message broadcasting and information isolation; Multi-Agent Formatter allows agents to distinguish different speakers; Structured Output ensures reliable parsing of agent decisions; Multi-Agent Orchestration coordinates multiple agents to act in turn according to rules; SSE Real-Time Push allows the front end to display game progress in real time; Human in the Loop enables human players to seamlessly join the game.

Next, we will break down the application of these key technologies in AgentScope within the Werewolf game.

ReActAgent is the core agent implementation provided by AgentScope, based on the ReAct (Reasoning + Acting) paradigm. It allows the LLM to not just “answer questions,” but to “think, act, and rethink”: first analyze the current situation, decide whether more information is needed from tools, execute those tools, and continue reasoning until a final conclusion is reached.

In Werewolf, each AI player is a ReActAgent that can remember previous discussions, analyze the logic of other players’ speeches and votes, and make reasonable decisions based on their roles.

ReActAgent werewolfAgent = ReActAgent.builder()

.name("Player 3") // Player Name

.sysPrompt(prompts.getSystemPrompt(Role.WEREWOLF, "Player 3")) // Role System Prompt

.model(model) // LLM Model

.memory(new InMemoryMemory()) // Conversation Memory

.build();Creating an AI player only requires a few lines of code, mainly consisting of four core configurations: name is the identifier for the player, indicating which player this ReActAgent corresponds to; sysPrompt defines the role identity and behavior strategy; model is the underlying LLM; and memory is responsible for storing dialogue history.

Prompt defines the agent's “character”. Here, the prompt for the werewolf role is as follows:

**[Role Identity]**: You are Player 3, a Werewolf.

**[Core Objectives]**:

- Hide your Werewolf identity and survive until the end;

- Mislead good players through your statements, and vote out special roles;

- Cooperate with your Werewolf teammates to create logical confusion during the day.

**[Strategy Selection]**:

Strategy A: Bold Werewolf (Impersonating the Seer)

- Claim Seer in the first round, giving false investigation results.

- Speak with firm confidence, accusing opponents of being "impostor Seers" (or "bold Werewolves").

Strategy B: Deep Cover Werewolf (Disguised as a Villager)

- Speak concisely, avoiding becoming the focus.

- Act like an ordinary villager earnestly trying to find Werewolves.The prompts for different roles vary significantly: werewolves need to learn to lie and cooperate, while prophets, witches, and hunters need to understand how to use their skills, and villagers must analyze logic to find flaws.

Each agent has an independent memory that records everything it has “heard” and “said.” When an agent calls call() to generate a reply, it first retrieves historical messages from memory as context to send to the LLM. In Werewolf, the role of memory is crucial: speeches from each round of discussion are written into memory, allowing the AI to review the entire discussion history and determine who’s speeches contain logical flaws and who has been leading the narrative.

ReActAgent encapsulates the LLM's capabilities into a player that can think and converse continuously. They can remember previous discussions, analyze other players’ speeches and voting logic, and complete the entire game under the guidance of the moderator.

The essence of Werewolf lies in the asymmetry of information—werewolves know who their teammates are, but good players do not. This presents challenges for multi-agent systems: discussions during the day, voting results need to be broadcasted to everyone; but the werewolves' nighttime scheming and the prophet’s verification results must be strictly isolated, visible only to specific roles.

If we manually manage each message recipient and write a bunch of if-else statements “this message should go to whom,” the code quickly turns into a chaotic mess. AgentScope’s MsgHub addresses this issue with message channels: different scenarios use different channels, each channel has its own participant list, and messages circulate only within their channel. Discussions among werewolves at night use a werewolf channel, while public discussions in the daytime use a public channel—naturally isolating between channels.

Another detail: the timing of message broadcasting is also crucial. During the discussion phase, players take turns speaking, and after each person speaks, the others need to hear that statement immediately; otherwise, the subsequent speakers won’t be able to analyze or respond to previous content—this requires real-time broadcasting. However, it’s different during the voting phase; if each person’s vote is immediately announced after they vote, the later players might end up following the votes of others. Therefore, voting content needs to be collected first, and then announced uniformly after everyone has voted. MsgHub supports both modes: automatic broadcasting for discussions, manual broadcasting for voting.

// Discussion Phase: Enable auto-broadcasting

try (MsgHub discussionHub = MsgHub.builder()

.name("DayDiscussion")

.participants(alivePlayers.stream()

.map(Player::getAgent).toArray(AgentBase[]::new))

.announcement(nightResultMsg)

.enableAutoBroadcast(true) // Auto-broadcast enabled

.build()) {

discussionHub.enter().block();

for (Player player : alivePlayers) {

// After each player speaks, automatically broadcast to all other players

player.getAgent().call().block();

}

}

// Voting Phase: Disable auto-broadcasting

votingHub.setAutoBroadcast(false); // First, disable auto-broadcast

List<Msg> votes = new ArrayList<>();

for (Player player : alivePlayers) {

Msg vote = player.getAgent().call(votingPrompt, VoteModel.class).block();

votes.add(vote);

}

// After collecting all votes, broadcast the results uniformly

votingHub.broadcast(votes).block();During the discussion phase, automatic broadcasting is enabled, and after the agent’s call() returns, it immediately pushes to other participants; during the voting phase, it turns off automatic broadcasting, and after all votes are collected, the results are announced through broadcast(). These two modes correspond to two types of message receiving for agents:

● Discussion phase: Each player actively speaks by calling call(), MsgHub automatically broadcasts that message to other players. Other players “hear” this message through the observe() method—messages are written into their memory, but they don’t need to reply immediately. When it’s their turn to speak, they call call() to analyze and respond based on all historical data in memory.

● Voting phase: After disabling automatic broadcasting, each player's vote won't be immediately known to others. Once everyone has voted, the results can be announced all at once through broadcast(). Here, the observe() method is also called, and players just need to know the results without needing to reply.

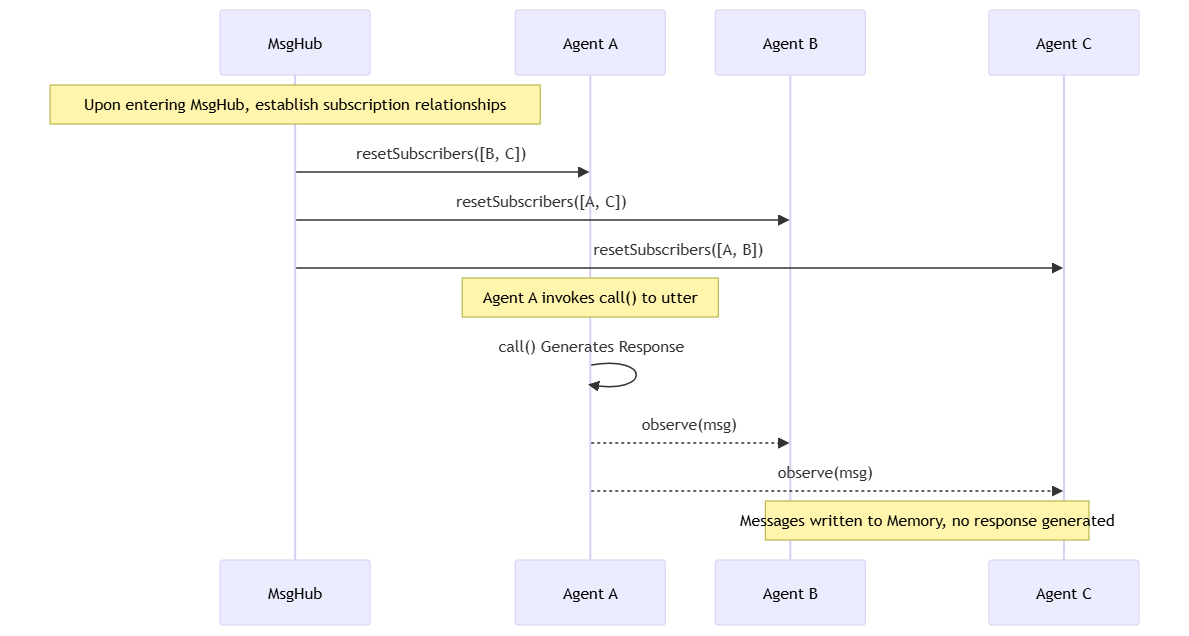

MsgHub realizes automatic message broadcasting between multiple agents based on the publish-subscribe model:

Based on MsgHub, we solved the real-time synchronization of the discussion phase using automatic broadcasting, the unified announcement of the voting phase with manual broadcasting, and the isolation of information in scenarios like werewolves scheming, prophet verification, and witch decision-making using multiple MsgHubs.

Multiple players take turns speaking, and each has their own stance and strategy. When Player 7 needs to analyze the situation, they must clearly know: the phrase “I am the prophet” was said by Player 3, and “he is an aggressive jump wolf” was said by Player 5. Only by differentiating who said what can logical deduction occur.

Most LLM APIs only support system、user、assistant three roles, lacking the concept of “Player 5” or “Player 7.” If we send all agents’ speeches as user messages to the model, what the model sees would look like this:

user: I am the Seer. Last night I investigated Player 5, and they are a Werewolf!

user: I am the real Seer! Player 3 is the impostor Seer! (or "Player 3 is a bold Werewolf!")

user: As Player 5's protected villager, I choose to side with Player 5.Three messages, three users—the model can't distinguish whether these are one person saying three sentences or three different people each saying one. Logical reasoning becomes impossible.

After introducing AgentScope's MultiAgentFormatter, agents can automatically understand multi-person speech dialogue. The messages sent to the LLM are automatically formatted as follows:

# Conversation History

The content between <history></history> tags contains your conversation history

<history>

Player 3: I am the Seer. Last night I investigated Player 5, and they are a Werewolf!

Player 5: I am the real Seer! Player 3 is the impostor Seer!

Player 7: As Player 5's confirmed good person (gold water), I choose to side with Player 5.

</history>

Now it's your turn to speak. Please analyze the situation.All conversation history is merged into one user message, with each speech prefixed by the speaker's name. The LLM can clearly see: Player 3 claimed to be the prophet and verified Player 5 for the kill, Player 5 countered that Player 3 is actually the aggressive jump wolf, and Player 7 chose to support Player 5. The logical chain is crystal clear.

Using the MultiAgentFormatter is very simple, just specify the formatter when creating the model:

DashScopeChatModel model = DashScopeChatModel.builder()

.apiKey(apiKey)

.modelName("qwen3-plus")

.formatter(new DashScopeMultiAgentFormatter()) // Done with a single line of code

.build();Once configured, all requests sent through this model will automatically undergo multi-person dialogue formatting without requiring manual handling in the business code. AgentScope provides corresponding formatters for popular models like Qwen, OpenAI GPT, Claude, and Gemini.

The formatter works in two key steps: message tagging and message merging.

Message Tagging: Each agent is assigned a name (like "Player 3") upon creation. When the agent generates a reply, the framework automatically sets the agent's name in the message's name field:

// Set the name when creating the Agent

ReActAgent.builder()

.name("Player 3") // ← This name is automatically bound to the message

.model(model)

.build();

// When the Agent generates a response, the framework automatically performs internally:

Msg responseMsg = Msg.builder()

.name(agent.getName()) // ← "Player 3"

.role(MsgRole.ASSISTANT)

.content("I am the Seer. Last night I investigated Player 5, and they are a Werewolf!")

.build();Thus, each message stored in memory comes with an identifier of the speaker; the formatter simply needs to read msg.getName() to know who said it.

Message Merging: Before sending to the LLM API, the formatter merges multiple messages in memory into a single tagged history. The original messages in memory look like this, each stored independently with a name field:

Msg(name="Player 3", content="I am the Seer. Last night I investigated Player 5, and they are a Werewolf!")

Msg(name="Player 5", content="I am the real Seer! Player 3 is the impostor Seer!")

Msg(name="Player 7", content="As Player 5's confirmed good person (gold water), I choose to side with Player 5.")

...(potentially dozens more)After processing through MultiAgentFormatter.format(), the message sent to the LLM API has only 2 messages:

[0] role: "system"

content: "You are Player 3, a Werewolf..."

[1] role: "user"

content:

"<history>

Player 3: I am the Seer. Last night I investigated Player 5, and they are a Werewolf!

Player 5: I am the real Seer! Player 3 is the impostor Seer!

Player 7: As Player 5's confirmed good person (gold water), I choose to side with Player 5.

</history>"Previously, we mentioned that the roles for LLM APIs only consist of three types; if nine people discuss for two rounds, that would result in 18 user messages, making it difficult for the model to clarify the relationships among these messages. By merging them into one, all dialogue history is presented as a whole, and each is in the name: content unified format, which enables the LLM to clearly understand the complete discussion context.

Simply by providing a MultiAgentFormatter when creating the Model object used for ReActAgent, the framework will automatically handle message tagging and merging, allowing the LLM to understand multi-person multi-party dialogue within the limitation of three roles. Developers don't need to concern themselves with the formatting details, allowing them to focus on business logic instead.

At each critical node in Werewolf, players need to make clear decisions: who to vote for elimination? Which player should the prophet verify? Should the witch use the antidote? These decisions must be definitive—“vote for Player 3” or “verify Player 5,” rather than vague expressions like “I think both Player 3 and Player 5 are quite suspicious.”

However, LLMs are inherently free text generators. If you ask it, “Who are you going to vote for?” it may respond, “After comprehensive analysis, I believe the player who has been silent is the most suspicious”—it goes on and on without telling you specifically which player to vote for. Even if you emphasize in your prompt, “please directly reply with the player number,” sometimes it will still slip in unnecessary information, outputting something like “Player 3 (because their speech logic is contradictory).” Parsing these varied responses can be a nightmare for the program.

AgentScope's Structured Output completely resolves this issue. You just need to define a Java class that describes the expected data structure, and the framework will automatically constrain the LLM to output strictly in that format, returning results that are directly Java objects without the need for any parsing code.

Example of daytime voting.

// 1. Define the voting model

public class VoteModel {

public String targetPlayer; // Voting target

public String reason; // Reason for the vote

}

// 2. Call the Agent using structured output

Msg vote = player.getAgent()

.call(votingPrompt, VoteModel.class) // Specify the output type

.block();

// 3. Directly retrieve type-safe data

VoteModel voteData = vote.getStructuredData(VoteModel.class);

System.out.println(voteData.targetPlayer); // "Player 5"

System.out.println(voteData.reason); // "His logic has obvious flaws"Structured Output is implemented based on the Function Calling mechanism, which converts Java classes into tool definitions, guiding the LLM to generate formatted responses through tool invocation.

The framework converts Java classes (like VoteModel) into JSON schemas, registering them as a temporary tool generate_response, allowing the LLM to invoke this tool to generate responses that conform to the specified format. The response is automatically validated and converted into Java objects; if it fails, it prompts for a retry and cleans up the temporary tools afterward.

● Type Safety: The returned result is directly a Java object, with IDE auto-completion and compile-time checks, eliminating concerns about spelling errors or type mismatches.

● Uniform Format: The model is constrained to output according to the JSON Schema, preventing chaotic occurrences like “sometimes it's target, sometimes it's vote.”

● Automatic Retry: If the model's output does not conform to the format, the framework will automatically prompt the model to correct and retry—no need for manual handling.

● Efficient Development: Just define a POJO class, and use the same mechanism for voting, verification, rescuing, and other decision points, without having to write parsing code in every place.

With the capabilities of ReActAgent, MsgHub, MultiAgentFormatter, and Structured Output, the next question is: how to link them together so that multiple agents can execute in an orderly fashion according to the rules of Werewolf?

The flow of a game of Werewolf can be summarized as: Night Phase → Day Discussion → Voting Exile, then determine victory and defeat; if not finished, proceed to the next night round. Each phase has finer processes, and each process node here corresponds to the technical implementations introduced earlier:

Night Phase - Werewolf Discussion: Create a MsgHub that only involves werewolves, enabling automatic broadcasting. The werewolves discuss in this “private channel” where good players cannot see. Finally, collect the votes of each werewolf through structured output to determine the kill target.

Night Phase - Divine Actions: The actions of the prophet, witch, and hunter are private, requiring no MsgHub—they directly call the corresponding agents. Verification results, rescue decisions, and other information are written directly into the agent's memory and are unknown to others.

Day Discussion: Create a MsgHub that includes all surviving players, adding the results from the previous night to the MsgHub. With automatic broadcasting enabled, players take turns speaking, and after each one speaks, others immediately “hear” it.

Voting Exile: Disable automatic broadcasting, sequentially call each agent, and collect votes through structured output. Once everyone has voted, collect and announce the results uniformly.

GameState is the global game status that records objective facts of the game—who is what role, who is still alive, what day it is, and who was killed last night. This information is maintained by the orchestrator, and in advancing the game, the orchestrator must continually query GameState to make decisions: what round is it, is it currently night or day, whose turn is it to act, and should the game end or continue?

GameState tracks the current round through currentRound, incrementing each time night falls. The orchestrator controls the transitions between phases, scheduling the werewolf discussion, the prophet's verification, and the witch's actions in fixed order at night; during the day, it traverses the list of surviving players, taking turns to speak and vote in seating order. After each phase ends, the orchestrator calls checkWerewolvesWin() and checkVillagersWin() to determine victory and defeat—if the werewolf numbers reach or exceed the good players, the werewolves win; if all werewolves are eliminated, the good players win; otherwise, the game continues into the next phase.

The core process of game orchestration includes: managing message broadcasting and isolation of multiple agents using MsgHub, collecting agent decisions with structured output, maintaining game state with GameState, and saving the dialogue context of each agent using Memory. The orchestrator acts as the central coordinator, scheduling the game to run in an orderly manner according to the rules.

The previous sections clarified the message flow between agents and the orchestration of game processes. Now AI can play Werewolf by itself, but we still can't see anything. We need to push the game’s real-time progress to the front end—allowing observers to follow the plot, as well as preparing for future human-AI battles.

We utilize Server-Sent Events (SSE) for real-time pushing: the server actively sends events to the front end without polluting; speeches and voting results can be delivered at the first moment.

To push the game to the front end, we first need an intermediate layer to collect various events generated during gameplay. GameEventEmitter assumes this role: the game orchestrator calls its emit method at each significant node (player speech, phase transition, voting results, player elimination, etc.) to emit events.

To allow observers to immerse themselves in watching and enjoy the fun of their reasoning, we designed two perspectives:

● Player Perspective: Real-time push, but information that should not be seen is filtered based on the roles of participants. The “villager perspective” can only see public information, while the “werewolf perspective” can see werewolves' discussions at night; by default, the observation uses the “villager perspective.”

● God Perspective: Saves all events without filtering, used for review after the game ends.

public class GameEventEmitter {

// Player's perspective: Real-time push (filtered by role)

private final Sinks.Many<GameEvent> playerSink =

Sinks.many().multicast().onBackpressureBuffer();

// God's perspective: Stores all events (for review/post-game analysis)

private final List<GameEvent> godViewHistory = new ArrayList<>();

private void emit(GameEvent event, EventVisibility visibility) {

// God's perspective: Unconditionally save

godViewHistory.add(event);

// Player's perspective: Filter by visibility

if (visibility.isVisibleTo(humanPlayerRole)) {

playerSink.tryEmitNext(event);

}

}

}During gameplay, observers receive the filtered event stream in real time through playerSink; after the game ends, they can retrieve the complete godViewHistory through the /api/game/replay interface, reviewing all hidden details—“So Player 5 really was the prophet!”

With the event emitter in place, the next step is to let the front end receive these events. Spring WebFlux natively supports SSE: Controllers return a Flux<ServerSentEvent>, and once the browser requests this endpoint, the HTTP connection remains open, allowing the server to push data at any time.

@PostMapping(value = "/start", produces = MediaType.TEXT_EVENT_STREAM_VALUE)

public Flux<ServerSentEvent<GameEvent>> startGame(...) {

GameEventEmitter emitter = new GameEventEmitter();

WerewolfWebGame game = new WerewolfWebGame(emitter, ...);

// The game executes asynchronously in the background, not blocking the SSE connection

Mono.fromRunnable(() -> game.start())

.subscribeOn(Schedulers.boundedElastic())

.subscribe();

// Convert the event emitter's output to SSE format

return emitter.getPlayerStream()

.map(event -> ServerSentEvent.<GameEvent>builder()

.event(event.getType().name().toLowerCase())

.data(event)

.build());

}This code does two things: first, it starts the game logic on a background thread, and second, it converts the output of emitter into SSE format to return. Every time the game logic emits an event, the browser receives it in real time.

The last step is for the front end to subscribe to this SSE stream. The browser's native EventSource API makes this very simple—after establishing a connection, register handlers for each event type, and upon receiving events, update the UI accordingly.

const eventSource = new EventSource('/api/game/start');

// Someone has spoken -> Append to chat history

eventSource.addEventListener('player_speak', (e) => {

const event = JSON.parse(e.data);

appendMessage(event.data.player, event.data.content);

});

// Phase has changed -> Update top status bar

eventSource.addEventListener('phase_change', (e) => {

const event = JSON.parse(e.data);

updatePhase(event.data.round, event.data.phase);

});

// Game has ended -> Display win/loss result, close connection

eventSource.addEventListener('game_end', (e) => {

const event = JSON.parse(e.data);

showGameResult(event.data.winner);

eventSource.close();

});The entire process is very straightforward: the back-end game logic generates events → GameEventEmitter filters and emits → Controller converts into SSE format → Browser receives and renders in real-time. No polling required, no complex handshake with WebSocket; a single HTTP long connection gets it all done.

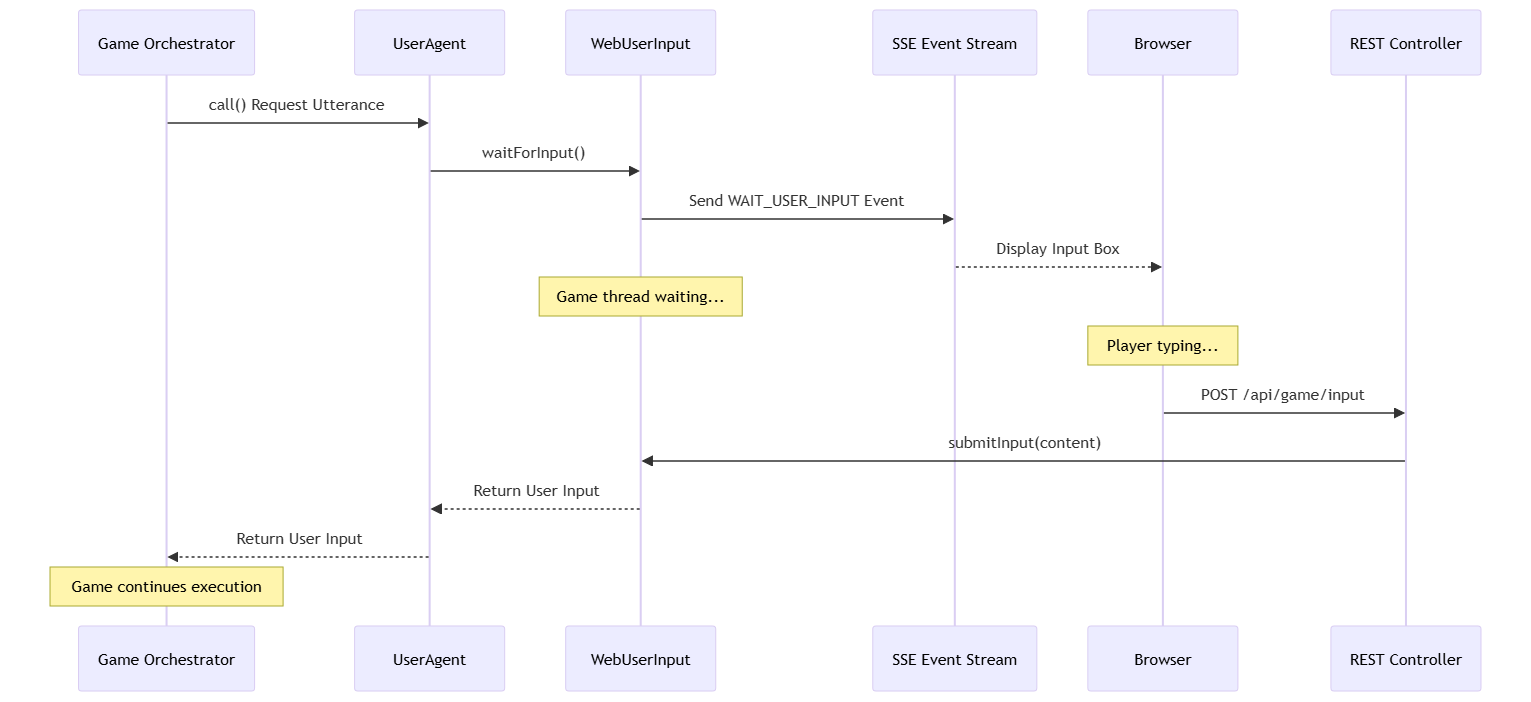

The previous sections pushed the game's progress to the front end using SSE, allowing us to observe the AI competition in real-time. However, simply watching is not enough; human players need to participate to create a proper game.

The game orchestrator can synchronously obtain results when calling agent.call(). AI players can return results promptly, but human players need to wait—waiting for the user to think, input, and submit in the browser. How can we “pause” the synchronous game flow while waiting for human players to input and then continue? AgentScope provides UserAgent to address this issue. It implements the same interface as ReActAgent, so the game orchestrator does not need to differentiate whether it’s dealing with a human or AI—it can call it in the same way. The specific method of obtaining the human input can be customized by injecting different UserInputBase implementations.

For the game orchestrator, there is no difference between human players and AI players—they both call agent.call() to get responses; the difference lies only in the configuration during creation:

// AI Player - Uses ReActAgent, responses generated by LLM

agent = ReActAgent.builder()

.name("Player 3")

.sysPrompt(prompts.getSystemPrompt(Role.WEREWOLF, "Player 3"))

.model(model)

.memory(new InMemoryMemory())

.build();

// Human Player - Uses UserAgent, responses provided by user input

agent = UserAgent.builder()

.name("Player 1")

.inputMethod(webUserInput) // Injects Web input source

.build();The benefit of this design is that the orchestrator’s code does not need to change at all; it simply replaces a ReActAgent with a UserAgent in some initializer locations to implement human-AI battles.

WebUserInput is the key component connecting the browser and game logic. Its core mechanism is implementing asynchronous waiting using Reactor’s Sinks.One:

public Mono<String> waitForInput(String inputType, String prompt) {

// 1. Create a Sink, similar to CompletableFuture

Sinks.One<String> inputSink = Sinks.one();

pendingInputs.put(inputType, inputSink);

// 2. Notify the frontend via SSE: it's your turn now

emitter.emitWaitUserInput(inputType, prompt);

// 3. Return a Mono, the game thread will wait here

return inputSink.asMono();

}

public void submitInput(String inputType, String content) {

// After the user submits, find the corresponding Sink and emit the value

Sinks.One<String> sink = pendingInputs.remove(inputType);

if (sink != null) {

sink.tryEmitValue(content); // Release the wait, game continues

}

}When it's the turn of the human player, waitForInput() sends a WAIT_USER_INPUT event to the front end via SSE and then returns a Mono which causes the game thread to wait. After the user inputs and submits in the browser, the front end calls the /api/game/input interface, and the controller calls submitInput() to emit the value, waking the game thread to continue execution.

The data flow in human-computer interaction can be summarized as: game waiting → SSE notifying front end → user input → REST submission → game continues.

Using this mechanism, you can choose any role to join the game: play as the prophet guiding the good players in reasoning or blend in with the werewolves, or even randomly pick a role. Now you don’t need to wait for everyone to gather; you can open it anytime and play a game with the AI.

Finally, let’s revisit the project overall, as we faced six core challenges: how to enable agents to think continuously rather than just answer once, how to implement information isolation between public discussions and private scheming, how to help agents understand who said what in multi-person dialogue, how to ensure agent decisions are reliably parsed by the program, how to allow human players to interact seamlessly with AI, and how to present the game progress in real-time to users.

To confront these challenges, we employed AgentScope's core capabilities one by one: ReActAgent grants each agent the ability to think continuously; MsgHub implements automatic broadcasting and information isolation; Multi-Agent Formatter enables agents to distinguish different speakers; Structured Output ensures reliable parsing of agent decisions; UserAgent allows human players to join games seamlessly; Streaming Output together with SSE real-time push makes the front end present game progress live.

Building on that, we also need to address game-specific orchestration and interaction issues: GameState maintains the global game state, supporting the entire game orchestration logic; AgentRun provides a runtime environment for agents; and Reactor Sink implements asynchronous waiting, enabling WebFlux applications to elegantly wait for user input.

The current implementation supports single-player against AI, but the allure of Werewolf lies in the psychological battles between players. Imagine: you and your friends join a game, probing each other and performing in the day discussion while AI players fill the remaining slots, allowing you to start without needing everyone to gather. A multiplayer mode will lead to a more authentic social deduction experience—after all, deceiving your friends is far more interesting than deceiving an AI.

While purely text-based conversations are efficient, they lack a bit of immersion. The Python version of AgentScope's Werewolf has already implemented TTS and real-time full modal support. Our next step is to introduce voice interaction in the Java version: you can speak directly, and AI players will also reply with voice—witches analyzing the situation calmly in a seductive voice, villagers with cute voices desperately proving their innocence, and low-voiced werewolves scheming at night. Each role will have a unique tone, turning the game from “watching conversations” into “listening to conversations,” as if you were actually sitting together playing a board game.

This project is a sample application for AgentScope Java, and we highly welcome community participation and contributions! Whether it's fixing bugs, optimizing experiences, adding new roles (idiots, guards, Cupid… ), or implementing the multiplayer and voice functionalities mentioned above, we look forward to your involvement. You can provide feedback on issues through submissions or directly submit a pull request to contribute code. Let’s work together to make this project better! Welcome to join the AgentScope DingTalk group, group number: 146730017349.

RUM-integrated End-to-End Tracing: Breaking the Mobile Observability Black Hole

648 posts | 55 followers

FollowAlibaba Cloud Community - April 2, 2025

Alibaba Cloud Community - September 10, 2025

Alibaba Cloud Community - January 26, 2025

Alibaba Cloud Community - May 16, 2024

Alibaba Clouder - March 27, 2020

Alibaba F(x) Team - September 1, 2021

648 posts | 55 followers

Follow Gaming Solution

Gaming Solution

When demand is unpredictable or testing is required for new features, the ability to spin capacity up or down is made easy with Alibaba Cloud gaming solutions.

Learn More Cloud Database Solutions for Gaming

Cloud Database Solutions for Gaming

Alibaba Cloud’s world-leading database technologies solve all data problems for game companies, bringing you matured and customized architectures with high scalability, reliability, and agility.

Learn More AI Acceleration Solution

AI Acceleration Solution

Accelerate AI-driven business and AI model training and inference with Alibaba Cloud GPU technology

Learn More Offline Visual Intelligence Software Packages

Offline Visual Intelligence Software Packages

Offline SDKs for visual production, such as image segmentation, video segmentation, and character recognition, based on deep learning technologies developed by Alibaba Cloud.

Learn MoreMore Posts by Alibaba Cloud Native Community