On November 18, 2025, an incident occurred, which was not caused by attacks or hackers, yet it paralyzed millions of websites all over the world. This incident was known to be caused by Vendor X, who triggered a chain reaction due to a seemingly minor database permission change, leading to the intermittent paralysis of its global edge network for nearly 4 hours. On that day, millions of enterprise websites and services that rely on the content delivery network (CDN), security protection, and serverless services of Vendor X experienced errors with 5xx HTTP status codes returned. At the same time, users were faced with an unexpected error that showed: "Sorry, we're unable to complete your request. Error 5XX". This severe interruption was not the result of an external threat, but was caused by a failure of internal configurations and automated processes. Here are some more alarming details:

● In the early stages, the incident was misidentified as a large-scale distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack.

● The status page went down, amplifying confusion and uncertainty.

● Core services, including CDN, access, and Workers KV, failed one after another.

● Ultimately, the root cause of the incident traced back to an exponentially growing "feature file" that exceeded memory limits.

This incident exposes a harsh reality: In modern IT systems, the most dangerous failures often arise from "normal changes" that produce "abnormal consequences". More than a technical failure, it serves as a mirror that reveals a fatal blind spot in today's digital architectures: People place excessive trust in the self-reported health signals of vendors, while neglecting to verify whether services are truly available from the perspective of the real world.

In this incident, the issues exposed by Vendor X are ones enterprises frequently encounter. Internal observability systems were overwhelmed with recording uncaptured anomalies, which in turn increased the CPU load. Console logons failed, and the status page became inaccessible, leaving O&M engineers unable to obtain a reliable view of the situation. Meanwhile, the global traffic exhibited a pattern of periodic recovery followed by collapse (every 5 minutes), further obscuring root-cause analysis. For enterprises that rely on such services, how can they respond quickly? Can traditional monitoring or observability tools prevent or mitigate similar incidents? The following table describes the monitoring approaches that enterprises typically rely on when they face upstream failures and the inherent limits of these approaches.

| Monitoring type | Ability to identify issues | Limits |

|---|---|---|

| Infrastructure monitoring | Unable to identify issues | Origin server resources are healthy. Issues occur at the edge layer. |

| Application performance monitoring (APM) | Able to identify partial issues | Only requests that reach applications are recorded. Traffic blocked at the frontend cannot be identified. |

| Log management | Unable to identify issues | Log collection agents may fail to report data. |

| Status page of the vendor | Unable to identify issues | The status page of Vendor X was unavailable during the incident. |

| Ping or traceroute | With preliminary notice supported | Basic connectivity can be tested, but HTTPS or business logic cannot be simulated. |

In addition to 5xx HTTP status codes, this incident also manifested classic soft outages: sharply increased response latency, logon authentication failures, abnormal access to KV storage, and false positives by protection rules. The service was not completely down, but it was unavailable. This creates a dilemma: Even if you want to verify whether the issues lie on our side, no trustworthy sources of data are available for you to use. Combined with the preceding table, the conclusion becomes clear: Enterprises must move beyond the passive mode of relying on the self-reported health signals of vendors and establish an independent, objective, and user-oriented verification mechanism. When vendors themselves cannot clearly explain what is happening, only third-party proactive probing mechanisms can tell whether services are available.

This is precisely the core value of Synthetic Monitoring. It does not care which CDN or Web Application Firewall (WAF) service you use, nor does it depend on any internal logs or APIs. Instead, it operates from the perspective of real users, actively validating the actual accessibility and performance of services. By using a distributed probing network across Internet service providers (ISPs), regions, and vendors, Synthetic Monitoring creates an independent verification layer that is decoupled from any single infrastructure, delivering a monitoring experience with "God's eye view". This service not only tells you where things are broken, but also helps explain why they fail.

Let's step into the perspective of a customer who has deployed Synthetic Monitoring and replay the key moments of this incident along the actual timeline.

| UTC time | What happened | What would happen with Synthetic Monitoring deployed |

|---|---|---|

| 11:20 | The network of Vendor X began to drop traffic, triggering a surge of errors with 5xx HTTP status codes. | Global alerts from Synthetic Monitoring nodes: Multiple probes across Asia, Europe, the Americas, and Africa simultaneously identify 5xx HTTP status codes or connection timeout errors from the monitored site. Then, multi-level alerts are triggered immediately, and notifications are sent by using methods including emails, text messages, instant messaging (IM), and webhooks. The alert information includes contextual data such as geographic distribution, trend of HTTP status codes, and Domain Name System (DNS) resolution status. |

| 11:25 | The issue was misidentified internally as a DDoS attack, and mitigation measures were activated. | False attack signals ruled out: The data shows synchronous anomalies across all regions, with no concentration of source IP addresses. Combined with normal DNS resolution and TCP handshake failures, the evidence strongly suggests an upstream network failure rather than a regional attack. |

| 11:30 | The dashboard of Vendor X became inaccessible. | Independent verification remaining available: Synthetic Monitoring does not rely on the infrastructure of Vendor X and continues to provide real-time dashboards, enabling the site reliability engineering (SRE) team to make decisions remotely. |

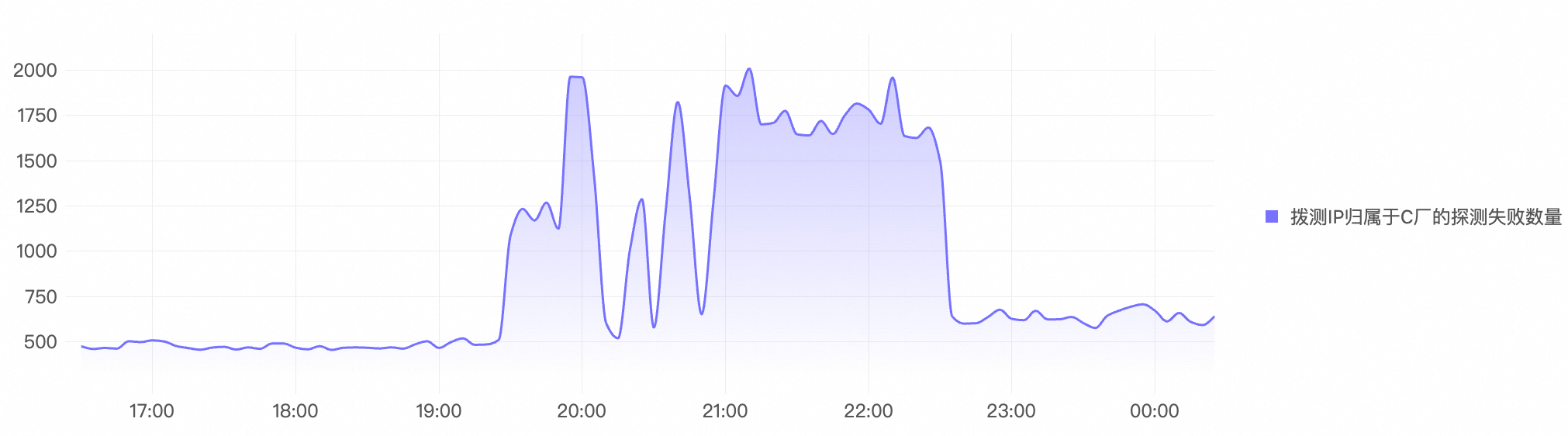

| 12:00 to 14:30 | The feature file was repeatedly regenerated, causing intermittent service recovery. | Precise identification of fluctuation patterns: The minute-level polling mechanism of Synthetic Monitoring clearly captures the repeated "up-down-up" cycles, visualized as alternating peaks and troughs. This highlights a non-persistent failure pattern and helps identify the root cause as configuration synchronization or automation issues. |

| After 14:30 | A normal configuration was manually injected, and services gradually recovered. | Automated recovery validation: After probing results show 10 consecutive successful checks and the response time drops below the baseline, the system automatically notifies teams that the P1 incident can be cleared, preventing human oversights. |

Based on the existing probing data, a large number of probing tasks destined for Vendor X began to fail during the incident.

With Synthetic Monitoring activated and multi-layer probing enabled, enterprises can quickly determine that the issue is not at the origin server, but rather a widespread failure at the edge proxy layer, and they can resolve the issue by taking actions such as switching to a backup CDN server or reviewing recent WAF configuration changes.

In real-world production environments, even the most mature internal processes cannot fully eliminate the risks introduced by human-driven changes. For most enterprises, the optimal solution is not to wait for vendors to become flawless, but to take control of business availability themselves. Beyond internal service observability, enterprises must rely on external validation to measure user experience, independently verify global availability, and form an effective availability protection net. Many people mistakenly equate synthetic monitoring tasks with periodically checking on a website. In reality, as enterprise systems continue to evolve, the Synthetic Monitoring service has grown into a comprehensive external validation toolkit. The following table describes its capabilities.

| Probing type | Capability | Scenario |

|---|---|---|

| HTTP or HTTPS probing | Custom headers, cookies, request body, and expected status codes | Simulated logons, API calls, and payment workflows |

| DNS probing | Resolution latency, authoritative server responses, and time to live (TTL) validation | Detection of DNS hijacking and cache poisoning |

| TCP or UDP probing | Port accessibility and handshake latency | Databases, game servers, and Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) services |

| SSL or Transport Layer Security (TLS) probing | Certificate validity, cipher suites, and Online Certificate Status Protocol (OCSP) responses | Early warning for certificate expiration |

| Step-by-step browser check | Real browser rendering with JavaScript execution | Single-page applications (SPAs), single sign-on (SSO), and CAPTCHA bypass testing |

| API transaction probing | Multi-step API orchestration with variable extraction and passing | Simulation of complete order creation workflows |

These different types of probes help analyze issues from multiple dimensions:

● DNS resolution latency spikes → DNS failures? Improper TTL configuration?

● TLS handshake failures → Certificate issues? Server Name Indication (SNI) blocking? Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) hijacking?

● HTTP status code distribution → Origin server errors? Edge gateway collapse?

● Regional discrepancies → Failures on specific point of presence (POP) nodes?

The most dangerous failures are not attacks, but losing service availability without realizing it. If user experience and business availability truly matter, enterprises must immediately ask themselves: When a vendor reports a failure, do we have an independent approach to verify it? Does our observability cover the actual access paths of real users? Do we have automated failover or degradation plans, and have we verified their effectiveness through probing? The value of Synthetic Monitoring lies precisely in its ability to tell users before a "storm" arrives. It does not replace internal monitoring, nor does it challenge the authority of vendors. Instead, it acts as a calm, objective, and tireless digital sentry, standing at the edges of the Internet and asking the most fundamental question: "Can I be accessed right now?" As long as this question has a clear answer, the business has a baseline of protection.

Never trust the thought of "it should be fine". Use evidence to prove that it truly is. That is the reason Synthetic Monitoring exists.

The AI Gateway Has Become a Symbol of AI Evolution This Year

Powered by Alibaba Cloud, POPUCOM Delivers a Zero-latency Adventure for Players Worldwide

639 posts | 55 followers

FollowAlibaba Clouder - June 17, 2020

AsiaStar Focus - September 9, 2022

Alibaba F(x) Team - June 21, 2021

Alibaba Clouder - June 18, 2020

Alibaba Clouder - July 10, 2020

Alibaba Clouder - June 24, 2020

639 posts | 55 followers

Follow IT Services Solution

IT Services Solution

Alibaba Cloud helps you create better IT services and add more business value for your customers with our extensive portfolio of cloud computing products and services.

Learn More Enterprise IT Governance Solution

Enterprise IT Governance Solution

Alibaba Cloud‘s Enterprise IT Governance solution helps you govern your cloud IT resources based on a unified framework.

Learn More Networking Overview

Networking Overview

Connect your business globally with our stable network anytime anywhere.

Learn More CloudBox

CloudBox

Fully managed, locally deployed Alibaba Cloud infrastructure and services with consistent user experience and management APIs with Alibaba Cloud public cloud.

Learn MoreMore Posts by Alibaba Cloud Native Community